1752

King George II confirmed the charter of the Two-Bit Club at the Court of St. James. Soon afterward, the name was changed to the South Carolina Society and began including non-French members.

1782 – Slavery

Capt. Joseph Vesey returned to Charlestown with his wife, Kezia, their son John and Vesey’s personal servant / cabin boy, sixteen year-old Telemaque.

1783

The first theatrical performance in Charleston after the British evacuation was held in the Exchange Building.

1800 – Slavery

A law was passed making it more difficult to emancipate slaves. Also passed was “An Act Respecting Slaves, Free Negroes, Mulattoes and Mestizoes” which permitted blacks to gather for religious worship only after the “rising of the sun and before the going down of the same … a majority [of the congregation] shall be white persons.”

Perhaps thinking that the “Christianization [sic] of the city’s black labor force would have a stabilizing effect,” the white authorities ignored late night church meetings among all black congregations for many years.

1826

The South Carolina Jockey Club was formed.

1860 – Secession

On this day, a secession convention meeting in Charleston, South Carolina, unanimously adopted an ordinance dissolving the connection between South Carolina and the United States of America.

Click here to read the Charleston Mercury’s account of secession.

Nina Glover, in Charleston, wrote to her daughter, Mrs. C. J. Bowen, “The Union is being dissolved in tears. The feeling exhibited was intense; each man, through the day, as he met his neighbor, anxiously asked if the Ordinance had yet passed.”

By mid-morning a large crowd of thousands had gathered on Broad Street in front of St. Andrew’s Hall. The Charleston police guard stood in front of the closed and locked doors.

The ordinance, written by Christopher Memminger, was a simple but direct statement. John Ingliss claimed that it meant: “in the fewest and simplest words possible to be uses … all that is necessary to effect the end proposed and no more.”

The call of the roll started at 1:07 P.M. and ended at 1:15, with every delegate voting “yea,” a unanimous vote – eight minutes to vote to “dissolve” the Union. From a window at St. Andrew’s a signal was flashed to the crowd. Then, according to Rev. Anthony Toomer Porter:

A mighty shout arose. It rose higher and higher until it was the roar of a tempest. It spread from end to end of the city, for all were of one mind. No man living could have stood the excitement.

The Mercury had received a draft copy of the ordinance, by 1:20 P.M., five minutes after the vote concluded, the “extra” was on the streets. During the day, tens of thousands of copies of the “extra” were printed. Perry O’Bryan’s telegraph office wired the news to the rest of the nation.

Upon the signing of the Ordinance, all the church bells in the city began to ring. James Petigru asked a passerby, “Where’s the fire?” The man responded, “Mr. Petigru, there is no fire; those are the joy bells in honor of the passage of the Ordinance of Secession.”

Petigru responded, “I tell you there is a fire. They have this day set a blazing torch to the temple of constitutional liberty, and please God, we shall have no more peace forever.”

Across the city, celebrations continued through the day. Elderly men donned the uniforms of their volunteer units and marched, shouting the news to all the neighborhoods. A man in a golden helmet trotted a horse around the city, a copy of the ordinance held aloft. Men gathered around Calhoun’s grave and vowed to “devote their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor, to the cause of South Carolina independence.”

The text of the Ordinance:

The State of South Carolina

At a Convention of the People of the State of South Carolina, begun and holden at Columbia on the Seventeenth day of December in the year or our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty and thence continued by adjournment to Charleston, and there by divers adjournments to the Twentieth day of December in the same year –

An Ordinance To dissolve the Union between the State of South Carolina and other States united with her under the compact entitled “The Constitution of the United States of America.”

We, the People of the State of South Carolina, in Convention assembled do declare and ordain, and it is hereby declared and ordained, That the Ordinance adopted by us in Convention, on the twenty-third day of May in the year of our Lord One Thousand Seven hundred and eight-eight, whereby the Constitution of the United State of America was ratified, and also all Acts and parts of Acts of the General Assembly of this State, ratifying amendment of the said Constitution, are here by repealed; and that the union now subsisting between South Carolina and other States, under the name of “The United States of America,” is hereby dissolved.

Done at Charleston, the twentieth day of December, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty.

Jacob Shirmer, a Union man like Petigru, prophetically wrote in his diary:

This is the commencement of the dissolution of the Union that has been the pride and glory of the whole world, and after a few years, we will find the beautiful structure broke up into as many pieces as there are now States, and jealously and discord will be all over the land.

Robert Gourdin wrote to John W. Ellis, governor of North Carolina:

Before the sun sets this day, South Carolina will have assumed the powers delegated to the federal government and taken her place among the nations as an independent power. God save the State.

We may, if possible, avoid collision with the general government, while we negotiate the dissolution of our situation with the Union. I apologize for the brevity of this … It is written at the dinner table amid conversation, wine and rejoicing.

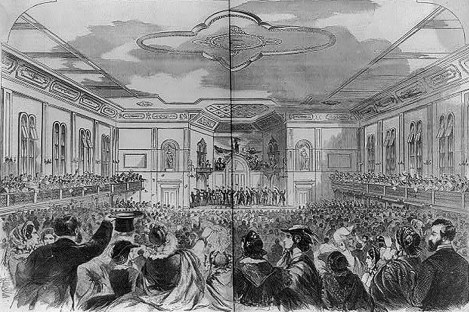

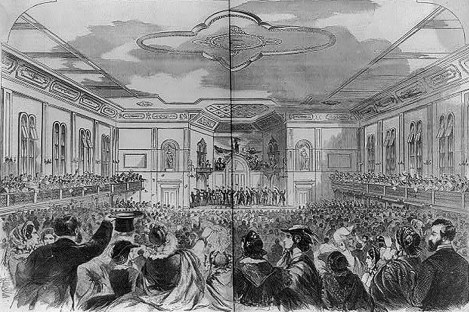

At 6:30 p.m. the secession delegates lined up on Broad Street in front of St. Andrew’s Hall, and through the gas lamp glow, marched east to Meeting Street, turned left and marched past Hibernian Hall, the Mills House and arrived at the front doors of Institute (Secession) Hall. The delegates entered the hall, to the roar of applause and cheers from more than 3,000 Charlestonians, packed into the building. One of the attendants was eighteen-year old Augustine Smythe, the son of Presbyterian minister, Rev. Thomas Smythe, who was crammed into the corner of the upper gallery. Also in the gallery was Virginian Edmund Ruffin and British consul Robert Bunch.

Photo of Meeting Street with 1806 version of Circular Church steeple and portico and SC Institute Hall, c 1860.

On the stage was a lone table, flanked by two potted palmetto trees. A banner on the stage read “Built from The Ruins.” After the delegates were seated, Rev. John Bachman offered a prayer where he asked God for “wisdom on high for the leaders … forced by fanaticism, injustice, and oppression” to secede. Then a copy of the ordinance, or, as the Mercury called it, “the consecrated parchment,” was read aloud and, as the Mercury breathlessly reported:

On the last word – “dissolved” – those assembled could contain themselves no longer, and a shout that shook the very building, reverberating, long-continued, rose to Heaven, and ceased on with the loss of breath.

South Carolina Institute Hall, street view, (Harper’s Weekly)

Upon the signing of the Ordinance of Secession, all the church bells in Charleston began to ring. James Petigru asked a passerby, “Where’s the fire?” The man responded, “Mr. Petigru, there is no fire; those are the joy bells in honor of the passage of the Ordinance of Secession.”

Petigru responded, “I tell you there is a fire. They have this day set a blazing torch to the temple of constitutional liberty, and please God, we shall have no more peace forever.” Late in the day, Petigru was again asked about secession and famously remarked, “South Carolina is too small for a republic and too large for an insane asylum.”

Inside South Carolina Institute (Secession) Hall. From Frank Leslie’s Newspaper. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

The ordinance was then placed on the stage table, and one-by-one, the delegates stepped forward to sign. Over the next two hours the delegates signed the Ordinance of Secession, and as politicians are apt to do, offered a few remarks on the “monumental occasion.” Ruffin wrote, “no one was weary, and no one left.”

After the last signature, Chairmen Jamison held the document above his head and exclaimed, “I proclaim the State of South Carolina an Independent Com-monwealth!” At that, the crowd rushed the stage, and frantically removed souvenir fronds from the palmetto trees. Augustine Smythe, slid down a pillar to the main floor, joined the scrum. He managed to not only get a palmetto frond souvenir, but also removed the pen and blotter used to sign the document. These items today are in the collection at the Confederate Museum, housed in Market Hall on Meeting Street.

The raucous celebration spilled into the Charleston streets, with men whooping and shooting pistols in the air. Bonfires in tar barrels, were lit on street corners across the city. Edmund Ruffin wrote, “The bands played on and on, as if there were no thought of ceasing.”

A teenager named Augustus Smythe procured a seat in the balcony of Charleston’s South Carolina Institute Hall on the night of December 20, 1860. Over the next three hours Smythe watched the members of the South Carolina legislature sign the Ordinance of Secession, officially removing the state of South Carolina from the Union and establishing an independent republic, ultimately called the Confederate States of America. The raucous celebration after that historic event spilled into the Charleston streets, with men whooping, drinking whiskey and shooting pistols in the air. Smythe had the calm foresight to make his way through the crowd to the stage and remove the inkwell and pen which had been used to sign the Ordinance. These items today are in the collection at the Confederate Museum, housed in Market Hall on Meeting Street.

Rally on Meeting Street, in front of Mills House, 1861. From Frank Leslie’s Newspaper. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

The foreign slave trade ended by Federal law, as negotiated during the creation of the U.S. Constitution. When the US Constitution was written in 1787, a generally overlooked and peculiar provision was included in Article I, the part of the document dealing with the duties of the legislative branch:

The foreign slave trade ended by Federal law, as negotiated during the creation of the U.S. Constitution. When the US Constitution was written in 1787, a generally overlooked and peculiar provision was included in Article I, the part of the document dealing with the duties of the legislative branch: