This is the entire sequence of events that took place in Charleston on June 28, 1776, from the forthcoming Charleston Almanac (East Atlantic Publishing).

1776, June 28. Rev. Cooper Prays for British Victory.

Rev. Robert Cooper prayed from St. Michael’s pulpit that “the King might be strengthened to defeat his enemies.”

1776, June 28. Battle of Sullivan’s Island.

Early that morning, Col. Moultrie rode on horseback from Fort Sullivan to Breach Inlet to consult with Col. Thompson. As he and Thompson were talking, they observed the British men-of-war vessels loosening their topsails, a sure sign they were preparing to get under way. Moultrie galloped the three miles back to the fort and ordered the drummers to beat the long roll. The 435 troops in the fort sprang into action to man their posts.

The detachment inside the fort was comprised of infantrymen of the Second South Carolina Regiment and 33 artillerists from the Fourth South Carolina Regiment. Moultrie’s staff included Lt. Colonel Issac Motte, Maj. Francis Marion, and Lt. Thomas Moultrie.

Marion was a severe taskmaster who did not tolerate nonsense. He kept the enlisted men busy upgrading the fortifications of the fort, alongside black slaves “whether they liked it or not.” He ordered no beer or rum purchased without “specific permission.”

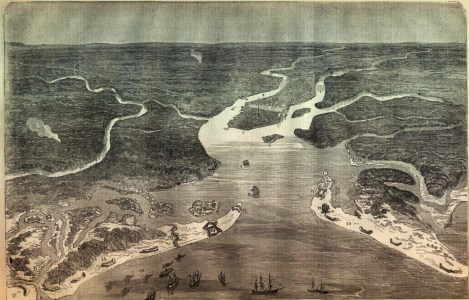

Charlestown harbor, 1776, with the British fleet approaching. Sullivan’s Island

to the right and Fort Johnson to the left, creating the narrow channel that ships

must pass through to enter the harbor. Courtesy of the New York Public Library

1776, June 28. Battle of Sullivan’s Island.

The first major naval battle of the Revolution commenced at 11:30 a.m. when the Thunder lobbed a thirteen-inch explosive mortar shell over the fort, which landed on the roof of the powder magazine. It failed to explode and did little damage. Had the shell not been a dud, the battle could have come to an abrupt conclusion with that one shot.

As soon as the British ships came into range, Moultrie opened fire with the guns on the southeast bastion. Moultrie termed the situation “one continual blaze and roar, with clouds of smoke curling over … for hours together.”

Although greatly outnumbered, and with vastly inferior armaments, the South Carolina troops kept the British fleet from entering the harbor. The British cannonballs embedded themselves in the pulpy palmetto logs with no damage to the fort. At the same time, Col. Thompson and his 400 men managed to hold The Breach, thwarting British efforts to cross and land troops on Sullivan’s Island. British soldiers, weighted down with their equipment trying to cross the Breach, sank in water above their heads.

Two hours into the fight, Gen. Lee, observing the battle at Haddrell’s Point, sent Maj. Francis Otway Byrd in a canoe to Fort Sullivan with a message to Moultrie, that “if the powder in the fort was expended” he should spike the guns and evacuate. To Moultrie, that was not an option. He was having good success and a retreat was unthinkable. Moultrie however, was running short of powder, having expended 4,766 pounds of the available 5,400 pounds. The situation was so dire that Moultrie ordered cannons fired at intervals of ten minutes for each gun, only when there was a clear target sighted. Moultrie sent Francis Marion with a small party to the armed schooner Defence and returned with 300 pounds of powder.

Maj. Byrd returned to Haddrell’s Point and informed Gen. Lee things were going “astonishingly well.” Encouraged, Lee contacted Pres. Rutledge, who sent 500 pounds of powder to the fort with a note, “Honor and Victory, my good sir, to you and our worthy countrymen with you.”

Seven miles away in the city, thousands of spectators watched the battle from waterfront vantage points or from rooftops and second-story piazzas.

Around 4 p.m. General Lee arrived at Fort Sullivan from Haddrell’s Point. To allow Lee’s entrance into the fort several of the Second South Carolina had to leave their guns and remove the timber that was barricading the back entrance. The British took that as a sign the fort was being abandoned. After inspecting the fort Lee told Moultrie, “Colonel, I see you are doing very well here, you have no occasion for me.”

Battle of Sullivan’s Island, June 28, 1776, two views. Courtesy of the New York Public Library

Three of the Royal ships, Syren, Actaeon and Sphinx, ran afoul of each other and grounded on a shoal called “Middle Ground” where Fort Sumter was eventually built.

In the midst of the battle, a British projectile broke the fort’s flagstaff. Sgt. William Jasper called out to Moultrie, “Colonel, don’t let us fight without our flag!” Moultrie, well aware of the audience watching in the city, asked Jasper what could be done. Jasper volunteered to retrieve.

He “leapt over the ramparts” and, shouted, “Don’t let us fight without a color!” Captain Horry described Jasper’s action:

He deliberately walked the whole length of the fort, until he came to the colors on the extremity of the left, when he cut off the same from the mast, and called to me for a sponge staff, and with a thick cord tied on the colors and stuck the staff on the rampart in the sand. The sergeant, fortunately, received no hurt, though exposed for a considerable time, to the enemy’s fire.

Moultrie wrote, “Our flag once more waving in the air, revived the drooping spirits of our friends; they continued looking on, till night had closed the scene, and hid us from their view.”

Sgt. Jasper replacing the South Carolina flag during the battle

of Sullivan’s Island. Courtesy of the New York Public Library

As American shot bombarded into the British men-of-war, one round landed on the Bristol’s quarterdeck and rendered Sir Peter Parker’s “Britches … quite torn off, his backside laid bare, his thigh and knee wounded.” The Acteon was grounded and severely damaged.

More than 2,500 British troops attempted to cross Breach Inlet from Long Island (Isle of Palms) to Sullivan’s Island. They were stopped due to the depth of the water, and the fire from Thompson’s troops on the Sullivan’s Island side.

By 9:30 p.m. Parker withdrew and Francis Marion fired the last shot from Fort Sullivan at the retreating Royal Navy. Moultrie sent word to Rutledge that the British ships had retired and that South Carolina was victorious. The reports came in from the ten-hour battle:

- British: 78 dead, 152 wounded. Lord William Campbell was wounded during the battle and later died of his wounds.

- American: 12 dead, 25 wounded. 5 died of their wounds later.

The Bristol had been hit seventy times.

1776, June 28. Declaration of Independence.

While the Battle of Sullivan’s Island raged, in Philadelphia Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams presented a final draft of the Declaration of Independence to the Continental Congress. While South Carolinians were exchanging shot-for-shot with the British Navy, the Declaration was read to the Congress.