With all the media furor over Bruce Jenner becoming Caitlyn, I thought this would be a good time to remind everyone that fifty years ago Charleston had one America’s most (in)famous transgender persons as part of our community – Gordon Langley Hall who became Dawn Langley Hall.

Bruce Jenner / Caitlyn Jenner

This story is taken from my 2006 book, Wicked Charleston, Vol. 2: Prostitutes, Politics & Prohibition.

“Charleston is a city with Gothic tales, and what they don’t know, they make up.” – Dawn Langley Hall

Charleston has always been a city that worships its past and is blindly proud of its Southern heritage. During the turbulent 1960s, Charleston was a city completely out of step with the times. Most people had yet to install air conditioning, in a city where today living without it is unfathomable for the tens of thousands of newly arrived residents. There were still a few black servants working for rich whites in their moldy mansions, while their not-so-well-to-do neighbors kept pigs and chickens in the yard behind their mansions.

In September 1962, a young English writer named Gordon Hall arrived in Charleston by chauffeured limousine. Gordon was accompanied by his parrot Marilyn, and his two pedigreed Chihuahuas – Nellie and Annabel-Eliza. Although Charleston was not known for its cold temperatures, Gordon had taken no chances and brought with him an electrically heated kennel for the dogs.

Gordon moved to arts-oriented Charleston with money to burn and a plan to take the city by storm. He had written several books, including biographies of Princess Margaret, Jacqueline Kennedy, and a critically acclaimed volume on Mary Todd Lincoln. Gordon soon became part of the social elite in Charleston, throwing lavish parties and attending most of the exclusive social occasions in the city. He claimed friendship with Hollywood legends Bette Davis, Helen Hayes, Joan Crawford, writer Pearl S. Buck and boxer Sugar Ray Robinson. His godmother was famed British actress Dame Margaret Rutherford, who lavished motherly affection on him.

However, in the life story of Gordon Hall nothing is as it seems.

Gordon Hall

In one of his autobiographies (yes, he wrote more than one), Gordon claimed he was born on October 16th, 1937 (although the gravestone says 1922) in Heathfield, England. Gordon was the illegitimate child of fifteen-year-old Margie Hall Ticehurst and nineteen year old Jack Copper, who had accomplished the notorious feat of having three women pregnant at the same time. Gordon claimed in one of his autobiographies that his mother was so shunned by her family she:

“locked herself in a darkened room for most of the nine months. One close and sadistic relative saw fit to kick her in the stomach.”

Sissinghurst Castle and Gardens

Gordon’s father, Jack, was the chauffeur of noted English poetess Vita Sackville-West who lived at Sissinghurst Castle, and his mother worked as a maid on the estate. From the earliest years, Gordon knew he was different. He was weak and had no interest in boyish pursuits.

“I hated sport, and I remember always having to miss gym; I couldn’t do the exercises.”

Whenever he was asked “Why don’t you like girls?” Gordon would answer that he was too busy with his writing. Gordon’s refuge from the world was writing. His first poem was published at age four and by age nine Gordon had a regular column in the Sussex Express.

Virginia Woolfe & Vita Sackville-West

Vita Sackville-West grew up in the largest house in England, Knole House, with 356 rooms and fifty-two staircases. In 1913, Vita married a young diplomat, Harold Nicolson, moved into Sissinghurst and the two began an unusual marriage. After giving birth to two children, Vita had several affairs with women, and Harold carried on with several men. The young Gordon was exposed to this wealthy, arts-oriented, sexually-open, eccentric household for most of his childhood. By the mid-1920s Vita had met the love of her life, the famous writer Virginia Woolf. Vita and Woolf personally encouraged Gordon, the son of their maid, to continue his writing.

One of Virginia Woolf’s most famous books was Orlando. The story follows the 300-year life of a young man who romances his way through the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries until finally during the1800s he suddenly changes into a beautiful woman and continues to have romances (this time with men), and eventually gives birth. The young Gordon Hall was mesmerized by the book, and also by Woolfe and Vita and their wealthy, unconventional lifestyle.

One of Virginia Woolf’s most famous books was Orlando. The story follows the 300-year life of a young man who romances his way through the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries until finally during the1800s he suddenly changes into a beautiful woman and continues to have romances (this time with men), and eventually gives birth. The young Gordon Hall was mesmerized by the book, and also by Woolfe and Vita and their wealthy, unconventional lifestyle.

At age sixteen Gordon decided to leave England. He took a job for a year as a teacher on an Ojibwa Indian reservation in Ontario. He also got a job as the obituary writer for the Winnepeg Free Press. In 1955, he moved to the United States and worked as society editor for the Nevada, Missouri Daily Mail. He remembered:

“They played it up that I was the first male society editor in the state of Missouri.”

One year later Gordon was living in New York City where his modern morality play, Saraband for a Saint, received congratulations from actresses Joan Crawford and Helen Hayes and prompted an invitation from the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Gordon at Isabel Whitney’s New York home.

While in Greenwich Village, Gordon stumbled into an art gallery where Isabel Whitney, a distant cousin, was having a show. Gordon and Isabel chatted and soon the 60-year old artist was so charmed by the young, frail Englishman that she invited him to her house for tea. “Visiting Isabel’s home was like entering some Tiffany cathedral,” Gordon later wrote. Within a few weeks Gordon moved into the forty-room Whitney mansion at 12 West Tenth Street, taking over most of the top floor.

Isabel Whitney was a descendant of Eli Whitney, inventor of the cotton gin, and her father had been one of the founders of the Paterson Silk Industry in New Jersey. She also claimed kinship with William Penn and Getrude Vanderbilt Whitney, one of the founders of the New York Museum of Modern Art. One of Isabel’s childhood playmates had been the young Franklin D. Roosevelt. Through Isabel’s patronage, Gordon was introduced to the elite of New York Society, including English actress Dame Margaret Rutherford, who had recently won an Oscar as best supporting actress for the film The V.I.P.s.

Gordon Hall & Dame Margaret Rutherford

Like Isabel, Rutherford and her husband, Stringer Davis, were childless, and soon Gordon was calling them Mother Rutherford and Father Stringer. It was from the encouragement of these women that Gordon wrote his humorous memoir about his days on the Ojibwa reservation, Me Papoose Sitter. The book sold well and was optioned for the Broadway stage. Gordon soon became quite a personality in New York art and social circles.

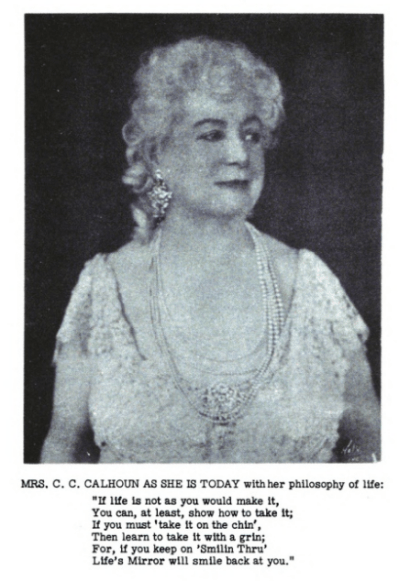

In 1959, Isabel was diagnosed with leukemia and for the next three years her condition worsened. Finally, in 1961, Gordon went looking for a house in the south with the intention of moving Isabel to the warmer climate to enjoy her final days. Gordon purchased a dilapidated mansion at 56 Society Street in Charleston. Two weeks later, February 2, 1962, Isabel Whitney died in her bed in New York. When her will was read, Gordon had inherited the New York mansion on West Tenth Street, art, jewelry, furniture and stock in Edison, General Electric, Standard Oil, and Sears. All told it was more than $2 million. “I was surprised to have been left so much,” he commented.

Gordon took the money, moved to Charleston by chauffeured limousine and restored the Society Street house in Ansonborough. He filled it with Chippendale furniture from the Whitney House. Other pieces included mirrors once owned by George Washington and bed steps belonging to Robert E. Lee. Quite a coup for the bastard son of a fifteen year old English maid and a nineteen year old wayward chauffeur.

“Queensborough”

Today Ansonborough is one of the city’s most prestigious communities, but when Gordon moved in, it was just shaking off a century of neglect. From its antebellum heyday, Ansonborough had taken a steady downward spiral so that by the 1960s, many of its mansions had been converted into tenements, flophouses, and shabby apartments. There were small corner groceries and tobacco shops. The neighborhood was a mixture of blacks, blue collar whites and a significant population of gay Charleston men – florists, hair stylists, decorators and restaurateurs.

54 & 56 Society Street, Ansonborough neighborhood, Charleston, 1960s

One of Gordon’s neighbors, Billy Camden, lived in Ansonborough in the 1960s. Camden was the owner of the gay bar, Camden’s Tavern, in the center of the city. He claims that:

The gay couples really restored Ansonborough. I was on the Board of Directors for the Ansonborough Historic Foundation – it was made of 80 percent gay men! There was a gay couple or person in almost every home. They should have called it ‘Queensborough’ instead . . .

During the antebellum days, Charleston’s gay aristocracy lived within the social customs of the time. Gay sons were expected to move away from the city so exposure of their sex habits would not embarrass their family. If they remained in Charleston, they must be completely discreet. During the 1960s most of the discreet men lived in Ansonborough. Even though the sexual revolution was in full flower throughout America, on the surface Charleston remained a very repressed sexual society. It was a curious fact that during that time many gay Charleston men were married with children. Gordon explained the custom this way,

“So many of the men in Charleston, especially the married men, walk two roads. They marry a rich society matron that might not be good looking, and try to find somebody on the side.”

Well before the Clinton Administration instituted the policy, Charleston society had a “don’t tell-don’t ask” rule of sexual behavior. If it could be ignored, most people didn’t care. Another of Gordon’s ‘Queensborough’ neighbors named Nicky, described 1960s gay life in Charleston.

We lived as ‘out’ as possible for that time period. We were socially active – visiting other gay couples for dinner, going to one of the town’s bars. We were also active in the larger Charleston community. Now, did other people know we were ‘gay’? Sure. Did we ever declare ourselves gay? No.

Gordon Hall with his pets.

Ansonborough’s reputation didn’t rest only on the presence of a large gay population. There also were several houses of prostitution in the neighborhood. The first night in his new home Gordon was awakened at midnight by a group of drunken sailors. Seeing the lights from the chandeliers in the front room, the sailors had mistaken the newly restored home for a just-opened bordello.

Five doors to the west of Gordon’s 56 Society Street address was the infamous Homo Hilton, home to drag queens, street people, drug dealers and sex hustlers of all types. Less than a block away was the Coffee Cup, a twenty-four hour lunch counter where most customers showed up after 3:00 a.m. It was the favorite place for breakfast for the denizens of the Homo Hilton, their last stop before dawn.

Other social clubs included the Ratskellars on Court House Square. The Anchor was a mixed bar (gay and straight). The 49 Club was gay up front, mixed in the back, and gambling on the second floor. For the single gay man (not in a committed relationship) there was always ample opportunity to pick up men, particularly Navy and Air Force men. The Battery and the Meeting Street bus stop, across the street from Citadel Square Baptist Church were popular places to pick up cruising men.

Within a month Gordon had settled in his home. Gordon claims that

The invitations from would-be matchmakers kept pouring in . . . leading hostesses gave suppers that I really dreaded. Always some poor husbandless girl was purposely placed beside me at the table. When I showed no particular interest in the feminine sex, there were those who decided that I must be homosexual.

1966 paperback version

Gordon followed the local custom of rich whites by hiring a black cook and butler. He also continued to write. He produced a biography of Princess Margaret which was followed by Golden Boats from Burma, a book written about a relative of Isabel Whitney – Ann Judson – supposedly the first American woman to visit Burma. Next, Gordon wrote Vinne Ream: The Story of the Girl Who Sculptured Lincoln, a juvenile biography about the sculptor who created the stature of Lincoln that stands in the U.S. Capital rotunda. This was followed by a book about Jackie Kennedy, and Mr. Jefferson’s Ladies, a portrait of the wife and daughters of Thomas Jefferson. Gordon later wrote Lady Bird and Her Daughters.

All of Gordon’s books were inspirational stories about women in the midst of self-discovery. It doesn’t take an over-educated psychotherapist to conclude that Gordon identified and empathized with these women, but that empathy didn’t keep him from picking up men on the streets of Ansonborough at night for sexual liaisons.

Billy Camden described his impressions of Gordon:

When he first came, everyone accepted him. He was small-framed, very effeminate guy with a thick English accent. At the beginning, the people connected with historic Ansonborough included him. But as soon as it got out what was going on – with all the blacks he entertained – that was the end of it! He would always be with a group of black, screaming queens. Charleston people would have nothing to do with him. He was an insult to the gay community; we were never friends.

Nicky, another Ansonborough man claimed that Gordon

“patrolled Meeting Street at night. He loved black men almost as much as he liked old ladies with money.”

According to John Zeigler, long time owner of the Book Basement in Charleston, Gordon would pick up:

“anybody who would have anal sex on him. He found men walking the streets, a lot of them on Meeting Street, in the area in front of Citadel Square Baptist Church. That was the cruising zone.”

Julian Hayes claimed to have a one-night stand with Gordon in 1963. They met at the local Greyhound bus station, in the bathroom there. Hayes followed Gordon home, less than three blocks from the bus station, to Society Street. When Hayes was asked about Gordon’s penis he commented:

“I was very much impressed. You see, he was built much bigger than the average man. He had a penis that was enviable.”

John-Paul Simmons

John-Paul Simmons

According to one account, Gordon met John-Paul Simmons in the late spring of 1967. John-Paul had a date with one of Gordon’s young female black cooks. John-Paul arrived late, and the cook had already left. Gordon answered the door instead. “He was a little smiling man,” Gordon wrote. ”He never once asked for the cook.” John-Paul returned the next day with an armful of flowers, and the secret affair began.

Secret because this was Charleston – the capital of slavery, the city that organized the Confederate States of America, the city that fired the first shot of the War Between the States. Because in the Charleston of 1967, blacks and whites did not engage in romantic sexual affairs, particularly a homosexual affair.

John-Paul & Gordon

For several months the two carried on their furtive courtship. John-Paul was poor, black and uneducated, a brutish, bulldog of a man. Gordon was rich, white, cultured and elite. He was frail, with fine features, gentle and quiet. An odder couple could hardly be found.

The Dawn of a New Life

On December 11, 1967, Gordon Hall arrived at John Hopkins, in Baltimore. During the five days he spent at the Gender Identity Clinic he met with seven doctors. By the end of the week Gordon was placed on estrogen tablets and told to dress as a woman immediately, in preparation for sexual reassignment surgery. He returned to Charleston and while in the house he began to dress the part of a woman. He also underwent electrolysis to eliminate body hair.

Gordon began to tell everyone that he was really a woman, had always been a woman. He claimed that as a result of the kick-in-the-belly his mother had endured during pregnancy he was born with a swollen clitoris which was misdiagnosed at birth as a penis by a poorly trained midwife.

Gordon claimed that his abnormally large clitoris and hidden vagina had been identified as a penis by the midwife, and for years he had lived with the physical agony of cramps and blocked menstruation. Gordon claimed that one morning his housekeeper arrived for work and discovered him lying in a pool of blood. He claimed he was rushed to the hospital and while the doctor was flushing out the blood he commented, “I can’t understand why this is not fresh blood.” Gordon claimed it was old menstrual blood that had been blocked for years.

Dawn Langley Hall

Gordon’s first public appearance as a woman was sitting in a car at a drive-in restaurant. Next, he went shopping at the Piggly Wiggly on Broad Street. Soon, he was making daily trips around the city in dresses and heels. However, there was a legal issue to deal with. Charleston had a city ordinance that prohibited one gender as going out in public dressed as the other. Gordon was afraid there would be an incident and he would be arrested. Gordon hired a lawyer to alert the authorities that he was going though the process of having sex change surgery so he would not be arrested.

John-Paul began calling Gordon “Dawn” – to signal the dawn of their new life.

On September 23, 1968, after successful surgery, Gordon woke from anesthesia in room B-403 of John Hopkins Hospital as a woman – Dawn Pepita Langley Hall. Pepita was the nickname of Vita’s grandmother, making the link between Vita, Virginia Woolf and Orlando public. The link between Gordon and Orlando was becoming more complete. Dawn said:

“Gordon was no more as far as I was concerned. I destroyed every photograph, burnt all Gordon’s clothes and had his name taken off my grandmother’s gravestone.”

Interviewed years later about the sex change surgery he performed in Gordon, Dr. Milton Edgerton commented about Gordon’s clitoris and vagina claim. “We saw no evidence of that,” Dr. Edgerton said. When asked if Gordon had a uterus and ovaries he said, “No, there was no suggestion of that.”

Nevertheless, the transformation from Gordon to Dawn shocked most of genteel Charleston society. Biographer Jack Hitt remembered her as:

“small and thin, Dawn favored knee length skirts, a pillbox hat, and a Dippity-Do hairstyle — a dowdy doppelganger of Jackie Kennedy.”

Dawn was welcomed back by many in Charleston society who tried to understand and be sympathetic. After all, she still had a lot of money and good family background. There were persistent rumors of her affairs with several prominent Charleston men. The dinner invitations now included seating arrangements next to eligible bachelors.

But not everyone was so accommodating. Many who had welcomed Gordon into their homes now shunned Dawn when they passed on the street or encountered her in the pews at St. Philip’s church. Even so, the dissenters were in the minority . . . until Dawn and John-Paul announced their engagement.

John-Paul and Dawn

At that time, the marriage of a black man and white woman was a crime in South Carolina. The state constitution prohibited the “marriage of a white person with a Negro or mulatto or a person who shall have one-eighth or more Negro blood.”

However, in 1967, the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled a similar Virginia law unconstitutional, so their marriage looked possible. Dawn hired a local African-American attorney named Benard Fielding to help obtain the license. Charleston’s first interracial marriage of record was set for January 22, 1969.

First however, three elderly Charleston society ladies came to call on Dawn at her Society Street house. As is the Southern custom, they brought food: an apple pie for Dawn and a watermelon for John-Paul. They sat down with Dawn and asked her:

“Why can’t you be like other proper white ladies who fall in love with their butlers? We marry a proper white man, and keep the black man on the side. Miss Hall, if you insist on going through with this disastrous union you will end up on a cooling couch.”

Jeremy Morrow, an Ansonborough resident stated that:

“back then, gay men did not date blacks, and we certainly didn’t ‘marry’ them. Sex between black and white was always behind closed doors.”

Another Charleston woman traveled all the way to England to beg Mother Rutherford to stop the marriage. True to form as a proper English lady, Mother Rutherford invited the Charleston woman to tea, but she refused to intercede in Dawn’s marriage. Word leaked to the British press and on the following Sunday the London News of the World ran a story that stated: ROYAL BIOGRAPHER TO MARRY HER BUTLER.

Princess Margaret asked Mother Rutherford is the story was true. Mother replied:

“What would it matter, if he were a good butler?”

She was later asked by Time magazine if she approved of the impending nuptials of her adopted daughter and her response was:

“Oh, I don’t mind Dawn marrying a black man but I do wish she wasn’t marrying a Baptist.”

She also later told Dawn that “A man worth lying down with is worth standing up with.”

Marriage

On January 23, 1969, the New York Times wrote:

British-born Dawn Pepita Langley Hall, who was writer Gordon Langley Hall before a sex change, was married tonight to John-Paul Simmons, her Negro steward. The bride, an adopted daughter of Dame Margaret Rutherford, the actress, has given her age as 31. The groom is 22.

The wedding was met with mixed reaction in Charleston. Dawn (and Gordon) had always attended St. Philip’s Episcopal Church in Charleston, established in 1680, but a bomb threat to the church convinced Dawn to hold the ceremony in her home on Society Street. Leading up to the ceremony, John-Paul was hanged in effigy around the city.

On the day of the ceremony, the local radio stations alerted listeners that Charleston’s wedding of the year (or any year) was to take place. Liz Smith, gossip columnist for The Daily News, called to find out if Dawn was going to be wearing the pearls that Mother Rutherford had given her. Joan Crawford sent a bouquet of yellow rose buds and commented, “The heart knows why.” Actress Helen Hayes wrote Dawn a letter of encouragement. “There is no racial or religious prejudice among people of the theatre.”

Mother Rutherford insisted, “No wedding march for you. I want ‘The Battle Hymn of the Republic’.” The ‘Battle Hymn’ was a Civil War anthem for Union troops, sung as they marched through the defeated South. Dawn chose the song purposely to show contempt for the Charleston white elite.

Wedding ceremony at 56 Society Street

A crowd gathered on Society Street. Curious onlookers mixed on the street with dozens of reporters, everybody shouting, jeering and cheering. There was a heavy police presence, alert for any violence. Dawn recalled that “the street was packed, their bodies rippling like waves.” According to Joe Trott, the florist for the wedding:

“People were hanging out the windows . . . cameras were rolling. The police department was there, the fire department. I was so scared I would get shot. I was trying to get on a solid wall in case anybody was a sniper from one of the rooms across the street.”

For the ceremony, Dawn wore a floor-length dress with appliquéd lace flowers. Two five-year old boys carried her ten-foot train. The dogs wore corsages. After the minister pronounced them “husband and wife”, the couple kissed for thirty-seven seconds. And then they stepped onto their piazza to wave to the cheering (and jeering) crowd.

Jet magazine ran a feature about Dawn and her African American husband. Newsweek ran a page-long story about the “anguished transsexual” and her “Negro garage mechanic.” The Charleston News & Courier announced the wedding on their obituary page.

Wedding announcement on the obituary page, Charleston News & Courier, Jan. 23, 1969

The British tabloid The People ran a month long serial about Dawn’s life. The story began with this spectacular claim:

A remarkable FACT had now been established. At The People’s instigation Mrs. Simmons was examined by one of Britain’s most eminent gynecologists at his Harley Street surgery. He stated: “Mrs. Dawn Simmons was probably wrongly sexed at birth. She has the genital organs of a woman capable of normal sexual intercourse, and she is capable of having a baby.” On the evidence of the report it is not impossible that she could become pregnant.

The newspaper withheld the name of the “eminent gynecologist.”

When the couple returned from their London honeymoon, a crate of wedding gifts had been delivered to their front yard. During the night the crate was ransacked and all the wedding gifts were destroyed. The next morning the local police chief arrived to personally ticket them for “littering and having debris blocking the sidewalk.”

The harassment continued. John-Paul was shot at three times on the street. Dawn was run down on Anson Street by an unknown driver, injuring her shoulder. The telephone rang incessantly with crank calls and death threats. Several callers delighted in telling Dawn they had seen John-Paul “consorting with other women”, which was true, since he did have several other girlfriends. Dawn’s Doberman pincher, Charley, was poisoned and the basset hound, Samantha, was killed by a hit-and-run driver.

John-Paul and Dawn in front of Charleston City Hall

Dawn had spent an incredible amount of money in a twelve month period. Two weddings, a trip to Europe, and the Ford Thunderbird she had purchased as John-Paul’s wedding gift. When he totaled that car, she bought him a second, and a year later, she purchased a third Thunderbird. Dawn refurbished her mother-in-law’s house. John-Paul also told Dawn he had decided he wanted to fish for a living, so she bought him a twenty-seven foot trawler, which he used for parties. The boat ended up abandoned in the marsh along the Cooper River.

Dawn then began to tell everyone that she and John-Paul were hoping to have a baby.

Terry Fox, former neighbor, remembers:

I came to Charleston in the late 1960s and moved to number 52 Society Street . . . two doors down from Dawn. I was twenty-three and comparatively naive. At the time, part of me thought of Dawn as being a worldly, sophisticated person, who wouldn’t have anything to do with me. And then there was the freak-show part of her . . . But she was always very gracious and friendly.

After one year of marriage, Dawn to decided to give herself a first anniversary party. Terry Fox remembered:

I walked in . . . and nobody was in sight. The place was stenchful, and overrun with dogs. Suddenly, Dawn descended the staircase, dressed in a full length, form-fitting red brocade dress, with long sleeves and wearing some kind of tiara.

According to Fox, the dining room was set up with beautiful silver pieces, tarnished, and the table was laden with lunchmeat in plastic wrappers from Piggly Wiggly – Oscar Meyer bologna, Kraft American cheese slices, and pickle loaf salami. Less than a dozen people attended, included several of Dawn’s gay friends and John-Paul’s mother.

In the meantime, John-Paul was continually unfaithful and fathered an illegitimate son. He was diagnosed with chronic schizophrenia, which often caused delusions and hallucinations. John-Paul began to hear voices and having conversations with a three-eyed woman from Mars he called “Big Girl.” Like other sufferers John-Paul began to experience thought interruptions such as laughing at a sad moment or becoming completely disoriented to his surroundings.

Dawn’s extravagant life proved too much for Charleston’s closeted gay community. Her interracial marriage also sparked racism in the black community. As Jack Hitt wrote:

“Typically when one crosses forbidden lines: interracial marriage, announcing one is gay, taking a lover from another religion or class, or even changing one’s sex at least there is a community on the other side waiting for you. But Dawn charged across so many borders at once that she slipped into a country where she was the only inhabitant.”

John-Paul & Dawn on Broad Street, in front of Washington Park

There was more trouble. In April 1971, the bank foreclosed on 56 Society Street. Dawn claimed that due to a mail strike in England she was not receiving her royalty checks. A friend, Richia Atkinson Barloga, who lived south of Broad Street, offered the pay the mortgage in full, but according to Dawn, Richia disappeared, literally. Richia later claimed to have been drugged by a man and taken to a local motel. She resurfaced ten days later after the Society Street house had been sold at auction. Dawn and John-Paul moved into a rented house at 15 Thomas Street, a far cry from their upscale Ansonborough address. Dawn carried her precious antiques and art work into a house with twenty-seven broken windows. Many in Charleston were smug in their assessment, a satisfying “I told you so!” in their minds, if not on their lips.

Then Dawn an amazing announcement. She claimed she was pregnant with John-Paul’s baby.

Where’d That Baby Come From?

For several months during the spring and summer of 1971, Dawn walked the streets of Charleston wearing maternity clothes. Terry Fox, neighbor and guest at the first anniversary party, recalled seeing Dawn walking the streets in maternity clothes and flat shoes. But others didn’t believe it. Some claimed she would a big belly beneath her dress one day, and a flat stomach the next. Someone claimed to see a military surplus blanket stuffed beneath Dawn’s dress. “She became something of a laughing stock,” Fox recalled.

Anna Montgomery worked at a baby store on King Street and waited on Dawn. Anna claimed in the Charleston Chronicle that when Dawn walked into the store to make a purchase, the women laughed. She looked like a pregnant woman, Anna said, but “he forgot to tie down the strings of a pillowcase stuffed with cotton.”

Dawn called those comments “wicked.” She claimed:

“I did used cotton wool pads. . . but because of the burning in the breasts.”

Dawn and Natasha

Dawn tried to interest newspaper and magazine editors in her pregnancy story, but no one cared. She was no longer an exotic story; more often she inspired pity. She was convinced that white Charleston wanted to kill her unborn half-black child. She claimed there were numerous threats against her, so she decided to move seven hundred miles north to Philadelphia to give birth at the University of Pennsylvania hospital – or maybe to better hide whatever deception she was trying to pull. John-Paul remained in Charleston, in the housing project home of his girlfriend and mother of his son.

According to a birth certificate on file at the Department of Health Vital Statistics in the commonwealth of Pennsylvania, on October 17, 1971, Natasha Marginell Manugault Paul Simmons was born. Dawn herself gets the birth date of her ‘daughter’ wrong in her late autobiography, citing it was October 15. The first time John-Paul saw Natasha he commented, “Whoever saw a blue-eyed nigger?”

Natasha’s birth certificate

After her return to Charleston, Dawn pushed Natasha up and down the streets in an old-fashioned British baby carrier just like the one the Queen had for Prince Charles. She kept the birth certificate handy to flash at all doubters. Many were not convinced, particularly men like Julian Hayes, who had once described Gordon’s penis as “enviable.” Even John-Paul wasn’t impressed. He knew exactly where Natasha came from – one of his girlfriends. He claimed:

“I’d been going with her for eight months –constantly had sex, sex, sex, all the time with this girl. She was about twenty-three. She got pregnant”.

John-Paul said that the girl’s daddy knew Dawn wanted a baby, and the daddy didn’t want his daughter to have an illegitimate daughter with a black man. When the girl went into labor, the girl checked into Roper Hospital as “Mrs. Simmons” at Dawn’s direction. Dawn gave the daddy one thousand dollars for the baby. Dawn flew to Philadelphia with the South Carolina birth certificate listing “Mrs. John-Paul Simmons” as mother of the child. Dawn showed up at the Pennsylvania vital statistics office with the infant in her arms and paperwork in her hand bearing her name.

Dan Rowan and Dick Martin, Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In.

Dawn’s announcement of the birth of her daughter became the fodder for TV comedians Dan Rowan and Dick Martin, hosts of the wildly popular Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In, a show with more than forty million viewers. The opening monologue contained the following exchange:

Dan Rowan: News flash: Charleston, South Carolina. Noted transsexual Dawn Simmons hast just given birth to a daughter.

Dick Martin: We can only hope she grows up to be half the man her mother was.

Dawn moved to upstate New York and rented a run-down, ten-room mansion in the Catskills. The New York Times published a story under the headline TRANSEXUAL STARTING NEW LIFE IN CATSKILLS. Less than year later, however, the Times filed a follow-up story that read:

Today, the house is an empty wreck. The owner has sued for $800 in rent. As of last week, the Simones[sic] were on welfare, living in a local hotel. Cash from the book that Mrs. Simmons was reported to be writing did not materialize. With no money for fuel, the family moved out ‘in the dead of winter’ . . . and the pipes froze and burst, flooding the premises.

Dawn’s writing career had been reduced to writing for The National Enquirer. John-Paul was in and out of mental health facilities, popping in-and-out of her life. Dawn said:

“I would never desert him. I always see that he has clothes, pocket money and everything he needs.”

In 1995, Dawn published her third memoir, Dawn: A Charleston Legend. Her first two, Man Into Woman and All For Love, had been published more than twenty years before. For several years she had been living in North Charleston in a federally subsidized housing project. She was also the devoted grandmother of Natasha’s three children. She published a novel, She-Crab Soup, which managed to sell seventeen copies in its first year publication.

Dawn Langley Hall Simmons, 1995

Dawn Pepita Langley Hall Simmons, the former Gordon Hall, died quietly on September 18th, 2000, of effects from Parkinson’s disease. The funeral took place at the chapel of the J. Henry Stuhr Funeral Home. Natasha placed a misleading announcement in the newspaper so that the funeral would not become a media circus. Her body was cremated and divided into three equal parts: one-third to a friend in New Hampshire, a third to England and the rest to Natasha.

It was the end of a real life Orlando. Virginia Woolf would have been proud.

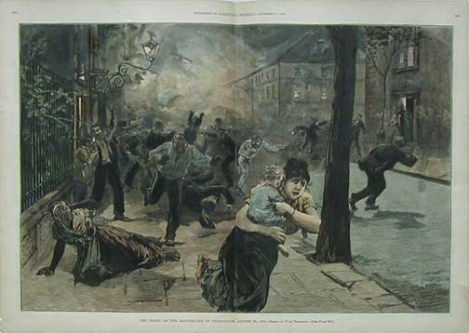

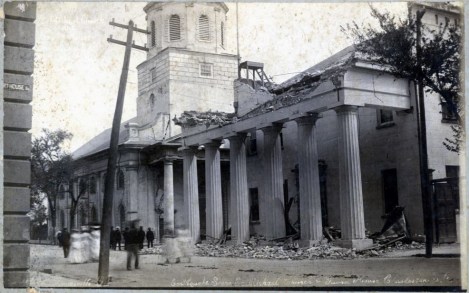

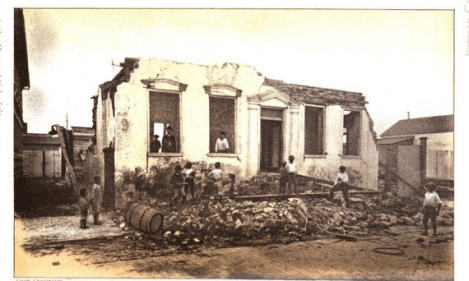

The following pages are taken from A Descriptive Narrative of the Earthquake of August 31, 1886 by Carl McKinley for the Charleston City Year Book 1887.

The following pages are taken from A Descriptive Narrative of the Earthquake of August 31, 1886 by Carl McKinley for the Charleston City Year Book 1887.