Excerpts from the book Wicked Charleston, Vol. II: Prostitutes, Politics & Prohibition

1876 Election

Leading up to the election, there were problems in Charleston. The Democrats considered the Reconstruction Republican government nothing more than a slave revolt, a challenge to their traditional white authority. They had created the Red Shirts, a white paramilitary group, to intimidate Republican, particularly, black voters. Wearing a red shirt became a source of pride and resistance to Republican rule for white Democrats in South Carolina. Women sewed red flannel shirts and other garments of red. It also became fashionable for them to wear red ribbons in their hair or about their waists. Young men adopted the red shirts to express militancy after being too young to have fought in the Civil War. The duly-elected Republicans, considered the Red Shirts and the less organized Ku Klux Klan as threats to the legal government. The federal government considered South Carolina to be just short of open rebellion.

The Port Royal Standard and Commercial (Oct. 5, 1876) wrote in an editorial:

“The entire Democratic party of the State is fully armed and organized . . . more dependence is placed in the shotgun than argument.”

The Democrats needed a man who could break the hold the Republicans had on state government, a man who could defeat the incumbent Republican, David Henry Chamberlain. Wade Hampton III was that man. Hampton was former Confederate Lt. General, from one of the richest families in South Carolina, and was one of the largest slave owners in the state before the war. His Republican opponent, Chamberlain, running for a second term, was born in Massachusetts and served as a second lieutenant in the United States Army with the Fifth Massachusetts Cavalry, a regiment of black troops. In 1866, Chamberlain had moved to South Carolina and quickly got involved in politics.

On Monday, October 16, 1876, a massacre took place at the Brick Church in Cainhoy outside of Charleston. During a Democratic meeting in the country, blacks began shooting from ruined houses and behind oaks at the assembled Democrats. Most of the white men were unarmed and those who were had nothing more powerful than pistols. Five whites and one black were killed, and twenty more were wounded. Most of the dead were mutilated and some of the wounded were not found until the next day, also maimed and mutilated, and left to die.

On Election Day, at 3:00 p.m., at the corner of Meeting and Broad Streets, E.W.M. Mackey was reading election news to a large crowd of Negroes. He finished and walked into the News and Courier offices on Broad Street. He got into a discussion with several white men who were watching the Courier’s election bulletin board. As they discussed the election, one of the men struck Mackey in the face; there was a scuffle and one shot was fired from a small French derringer. Negroes on the street rushed to the intersection of Meeting & Broad and shouted that Mackey had been killed. Less than five minutes later a mob of fifty Negroes was charging down Broad Street. The white men fired guns from the south side of Broad. The Negroes retreated to the north side, past City Hall. The police dispersed the crowd quickly and some of the black police went inside the Guard House and came out carrying Winchester rifles. They opened fire on the whites in the street.

The first victims were George E. Walter, a local businessman, and his son Endicott. They were returning from dinner to their office on Adger’s Wharf, walking on the north side of Broad in front of the courthouse. Endicott was killed and his father severely wounded. Dr. Cassimer Patrick, standing next to a column of St. Michael’s church, was also shot. Soon more than 1000 Negroes were in the street, carrying sticks and clubs. They stormed the front doors of the Guard House, shouting “Give us the guns!”

Red Shirts at the polls

The police sent word to Citadel Green, where U.S. troops were quartered. By 5:30 p.m. five hundred men had assembled, organized and together with the U.S Army, they brought the city under control, four hours after the riot began. The next day, all stores were closed, and schools were suspended. Rifle club members and the U.S. Army had every intersection guarded. The casualty of this riot included: one killed, twenty-two men shot or beaten, including two policemen. News and Courier editor Francis Dawson was also injured, shot through his calf as he rode through the mob on Broad Street.

The riot delayed the election returns in Charleston. On November 10, 1876, the final tally came in: Wade Hampton (D): 92,261; Chamberlain (R) 91,127. It appeared that Hampton had defeated Chamberlain by less than 1200 votes. However, each party claimed victory, accusing the other of fraud.

PITCHFORK BEN

Benjamin R. Tillman, an Edgefield County farmer, was born August 11, 1847, the youngest of eleven children. When Ben was two his father died of typhoid fever and his mother assumed management of the farm as well as the family inn-keeping business.

Young Ben helped his mother run the Inn and managed the farm, which included sixty-eight slaves. He enlisted in the Confederate army in 1864. However, an abscess in his left eye socket became inflamed and in October 1864 a doctor removed his eye and he was released from military duty.

Tillman learned politics during Reconstruction. He hated Republicans and Negroes who were not subservient. He supported any candidate who wished to “redeem” the state from Republican rule. Tillman became commander of the Sweetwater Saber Club and conducted a small-scale war against Negroes which included harassment and assault. He was involved in the execution of a black state senator, Simon Coker. Two of Tillman’s men executed Coker as he was kneeling with a shot to the head. A second shot was needed just in case he was “playing possum”. Tillman believed that the death of two blacks for the death of one white man was not enough payment. Evidently, seven was enough, for that was how many were blacks Tillman said should be killed in retaliation of the death of a white man.

Tillman helped elect Wade Hampton in 1876 as part of the Red Shirts and believed that a reformed Republican was no better than a corrupt Republican. They were both guilty of trying to endow blacks, something Tillman could not accept. He worked hard to rid South Carolina of the Republican / Yankee rule. Tillman admitted that the red shirt campaign was “a settled purpose to provoke a riot and teach the Negroes a lesson [by] having the whites demonstrate their superiority by killing as many of them as was justifiable.”

Ben Tillman

However, Tillman was soon disillusioned by Hampton and the Red Shirts; he believed they had formed an aristocratic cabal of conservative politicians and governed for the interests of antebellum low country planters and Charleston merchants. Tillman believed the interests of common poor white farmers in the upcountry and mill workers were being ignored. At the State Agricultural and Mechanical Society he lambasted state government as being “General This and Judge That and Colonel Something Else”. Tillman said Governor Hampton was responsible for all the problems in the state except “the 1885 hurricane and 1886 earthquake.”

Tillman began to attract statewide attention through his diatribes against blacks, bankers and aristocrats who he claimed were running and ruining the state. Tillman believed that farmers were “butchering the land by renting to ignorant lazy Negroes”. He called the graduates of the College of South Carolina (University of South Carolina) “drones and vagabonds”. He decried the fact that only eight statewide politicians were farmers. He called for the establishment of an agricultural college due to the failure of the College of South Carolina to produce statesmen necessary to “rebuild our shattered common-wealth”. He said the college’s agriculture department produced “theorists and cranks – book farmers”. Thus a separate college was needed. It became Clemson University.

Tillman claimed that “up to the period of Reconstruction, South Carolina never had real popular government.” The parish system of government gave the preponderance of seats in the Assembly to the low country. It insured “the absolute domination of the city of Charleston. A prouder, more arrogant, or hot-headed ruling class never existed.”

During the 1890 campaign for governor, Tillman was invited to Charleston to speak. Tillman hated Charleston, but he knew the city controlled the most powerful political machine in the state. Many who lived in the upcountry were more conservative and religious and looked down on Charleston. Ben Robertson wrote in Red Hills and Cotton (1942) that Charleston had been “hard on us for a hundred and ten years”. Charleston was “a worldly place . . . sumptuous, with the wicked walking on every side.”

Tillman addressed a crowd of several thousand from the steps of City Hall and called the crowd they were cowards for submitting to the tyranny of elite rule. He began thus:

You Charleston people are a peculiar people. If one-tenth of the reports that come to me are true, you are the most arrogant set of cowards that ever drew the free air of heaven. You submit to a tyranny that is degrading you as white men . . . If anybody was to attempt that thing in Edgefield, I swear before Almighty God we’d lynch him . . . You are the most self-idolatrous people in the world. I want to tell you that the sun doesn’t rise and set in Charleston.

Over the next hour he called Charleston the “the greedy old city”. He derided the citizens as “broken-down aristocrats” who viewed the world through “antebellum spectacles” and who “marched backwards when they marched at all”. He denounced “that niggerdom” of the low country. Then he went after Francis Dawson, editor of the News and Courier.

You are binding yourselves down in the mire because you are afraid of that newspaper down the street. Its editor bestrides the state like a colossus, while we petty men, whose boots he ain’t fit to lick, are crawling under him . . . He is . . . clinging around the neck of South Carolina, oppressing its people and stifling reform.

The next day in the paper Francis Dawson described Tillman as “the leader of the adullamites, a people who carry pistols in the hip pockets, who expectorate upon the floor, who have no tooth brushes and comb their hair with their fingers.”

As blacks began to lose their grip on political power, violence against them increased. Lynchings throughout the state became commonplace. Any white woman who accused a black man of rape was essentially giving him a death sentence. The Newberry Herald considered rape of a white woman by a black man too serious to merit the niceties of a legal trial. Elizabeth Porcher Palmer wrote that she hoped it (lynching) would “have a good effect”. In 1889, a mob of whites stormed the Barnwell County jail and murdered eight black prisoners accused of murdering a white man.

During the period of 1882-1930, there were over 150 lynchings in South Carolina, only six of the victims were white. During the 1890s four of the state’s congressional delegation had killed someone. Pistols were considered part of a man’s uniform – rich or poor, black or white. A state judge called South Carolina “an armed camp in a time of peace”. One of Tillman’s goals was the disenfranchisement of blacks. He stated that

We do not intend to submit to Negro domination and all the Yankees from Cape Cod to hell can’t make us submit to it . . . we of the South have never recognized the right of the Negro to govern white men, and we never will.

After winning the 1890 election for governor, Tillman supported his long-time State House colleague John Ficken for mayor of Charleston. Ficken was Charleston-born, graduated from the College of Charleston, served in the Confederate government, and studied law at the University of Berlin. He was a member of the local Democratic establishment, as were his closest friends. Together, they built up a strong coalition of uptown working-class labor groups. They exploited the long-simmering hostility toward the Broad Street Ring, run by local elites and gentry. Ficken was elected mayor in November 1891. His police chief was an upcountry friend of Gov. Tillman, Elmore Martin. Tillman, already disdained by most white elite Charlestonians, was now viewed with hostility.

In 1894 Tillman ran for the U.S. Senate. He called President Grover Cleveland “an old bag of beef” and was elected by a large majority. In 1902, Sen. Tillman physically attacked the other South Carolina Senator, John McLaurin. The two men fought on the Senate floor. Tillman ended up with a busted nose and McLaurin had open wounds on his face. Tillman was officially censured by the Senate. Even though he publicly apologized, he later claimed in a letter that “his constituents were delighted”. Tillman refused to change his crude manners or rough language. He claimed it was the only to combat “Republican rascality and Democratic imbecility”. Religious people complained about his profanity. He admitted it could not be controlled and from his viewpoint it was not a defect. He thought it was harmless against the drunkenness and adultery of other politicians. Gambling, smoking and drinking were worse vices than swearing. He was called the “Huck Finn of the Senate” and is now considered by historians to be one of the worst characters to ever serve in the United States Senate.

JOHN P. GRACE – The 1911 Revolution

John Patrick Grace was born on December 30, 1874. His father died when he was still a child, and he helped support his family by carrying milk deliveries from a cow that his mother kept. Ironically, one of Grace’s accomplishments as mayor was the outlawing of cows in the city for sanitary reasons. Grace left high school to start his own business and started a law practice in 1902. He ran for the South Carolina Senate in 1902 but lost and lost again in 1904 when he ran for county sheriff and again in 1908 in a race for the United States Senate.

Grace ran for mayor of Charleston in 1911 against businessman Tristram T. Hyde who was supported by the powerful “Broad Street Ring,” the traditional elite Charleston white business and political establishment. The Post And Courier actively campaigned against Grace, urging folks to “prevent dishonesty by voting for Hyde.”

Grace campaigned on a platform to modernize Charleston. Mildred Cram had recently written: “Charleston has resisted the modern with fiery determination … caught in a dream of the romantic past.” Grace understood that the elite underestimated the anti-Broad Street sentiment among Charleston’s white working-class voters; they wanted to embrace the future. During his speeches Grace called the Charleston elites “perjurers, thieves, aristocratic phonies and broken down social climbers.” His campaign against the establishment also included the Prohibition Drys, who wanted to outlaw liquor sales in the state.

On election day, Nov. 7, 1911, while Hyde remained in his headquarters, Grace spent the day visiting every polling place shaking hands. Fistfights broke out at several polling places, and a Grace supporter was arrested. Grace received 2,999 votes to 2,805 for Hyde. He called it “the Revolution of 1911.” One of his first acts was a large street improvement program, paving, new sidewalks, curbs and drains. Major streets were paved with asphaltic concrete.

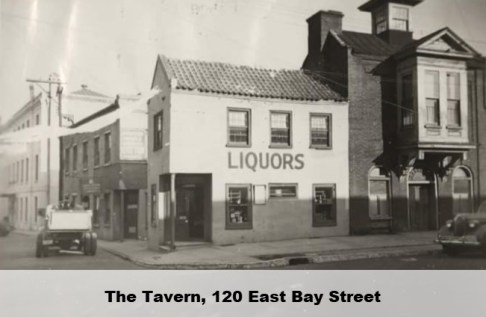

In 1913 Mayor Grace testified that Charleston had 250 Blind Tigers (illegal saloons) for a population of about 60,000 inhabitants. He bragged that he had instituted a system where the city fined each liquor operator and bordello $50 every three months. Mayor Grace claimed that it was a fair system. “If I wanted, I could fine them every time they sell a drink,” he said. He made no effort to shut down saloons and bordellos. The fines provided thousands of dollars for the city treasury. In fact, without the liquor and prostitution fines, the city budget would have been in the red. The mayor rarely ordered raids on Blind Tigers, and then it was “just for show.” He claimed that “Blind Tigers are too much of the web of life to close them down.”

In 1915, Hyde challenged Grace again, who was now considered an out-of-control radical populist by the Charleston elites. Grace was called “the mayor of graft” due to his relationship with the liquor trade. His response: “It’s the government’s job to prevent crime, not sin.” There was also an anti-Catholic campaign aimed at Grace.

Supported by former Mayor R. Goodwyn Rhett, Hyde won by 14 votes. Grace demanded a recount with representative of both campaigns guarding the sealed ballot boxes. On October 15, a recount was held in a small room on the southwest corner of King St. and George St. Police were on hand to keep order, but as the counting began, armed partisans of both campaigns rushed into the room. Shots were fired and Sidney J. Cohen, a young Evening Post reporter, was killed. Two ballots boxes were hurled out a window onto the street, with the ballots scattered on the breeze. Hyde was declared the winner, 3,109 to 3,081 and Grace conceded. He later stated that Sheriff Martin, a tool of the Broad Street Ring, “was willing and eager to have the streets of Charleston drenched with blood of her defenseless people it that would secure the election of Hyde.” He claimed that Martin’s deputies had instigated the shooting and tossed the ballots out to ensure there was no accurate recount.

That same year the Drys won a state-wide referendum ending all legal sale of alcohol within the state, four years before national prohibition took effect. However, the referendum did not repeal the “Gallon-a-Month” law, which permitted the importation into the state one gallon per person per month.

In 1919, Grace and Hyde squared off again for the third consecutive election. It was the closest mayoral race in the city’s history: 3,421 – 3,420, with Hyde as the winner. Grace challenged hundreds of ballots and managed to get 36 of them removed, which gave the election to Grace. He allowed the brothels to reopen, and in response to Naval officials complaining about the high rate of venereal disease, Grace instituted medical exams for prostitutes.

The 1923 mayoral election between Grace and Thomas P. Stoney was a wild affair. Stoney, a successful lawyer, had the support of the Broad Street political ring. He appealed to women voters by asking two women to run on his slate. He was a good speaker, entertaining with a good sense of humor.

Mayor Grace linked Stoney with the anti-Catholic KKK. Stoney called Grace a corrupt political boss who was hated elsewhere in the state. Two days before the election, Governor McLeod ordered the National Guard to assist the police in keeping order at the polls. This killed any chance of a Grace victory, since Grace’s political machine was masterful at poll manipulation. Grace called the use of soldiers “military despotism.”

William Watts Ball wrote that:

“Outsiders gaze upon a Charleston election with wonderment, sometimes with merriment.” An election in Charleston was “a scene of reveling, and immorality, a debasing struggle of bribery, corruption and intrigue.”

Stoney became the youngest mayor in Charleston history at age 34. He and his Broad Street law partners wielded large influence; they could promise any bootlegger immunity from prosecution as long as they were willing to pay the proper fees.

Available from Amazon.