1752 – Births

William Washington was born in Stafford County, Virginia. He was second cousin to George Washington and would later play an important role during the Revolution in South Carolina.

Washington was elected a captain of Stafford County Minutemen on September 12, 1775, and became part of the 3rd Virginia Regiment, Continental Line on February 25, 1776, commanding its 7th Company. His lieutenant and second-in-command was future President of the United States James Monroe.

On November 19, 1779, was transferred to the Southern theatre of war, and marched to join the army of Major General Benjamin Lincoln in Charleston, South Carolina. On March 26, Washington had his first skirmish with the British Legion, under command of Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton, which resulted in a minor victory near Rantowle’s Bridge on the Stono River in South Carolina. Later that same day, during the fight at Rutledge’s Plantation Lt. Col. Washington again bested a detachment of Tarleton’s dragoons and infantry.

During the Battle of Cowpens, January 17, 1781, Washington’s cavalry was attacked by Tarleton’s forces again. Washington managed to survive this assault and in the process wound Tarleton’s right hand with a sabre blow, while Tarleton creased Washington’s knee with a pistol shot that also wounded his horse. For his valor at Cowpens, Washington received a silver medal awarded by the Continental Congress executed under the direction of Thomas Jefferson.

September 8, 1781, the Battle of Eutaw Springs was the last major battle in the Carolinas, and Washington’s final action. Midway through the battle, Washington charged a portion of the British line positioned in a blackjack thicket along Eutaw Creek. The thicket proved impenetrable and British fire repulsed the mounted charges. During the last charge, Washington’s mount was shot out from under him, and he was pinned beneath his horse. He was bayoneted and taken prisoner, and held under house arrest in the Charleston area for the remainder of the war.

The British commander in the South, Lord Cornwallis, would later comment that “there could be no more formidable antagonist in a charge, at the head of his cavalry, than Colonel William Washington.”

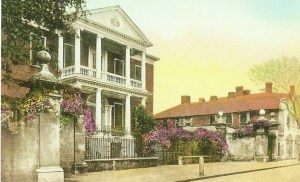

After the war Washington married Jane Elliott of Charleston and for the remainder of his life lived at 8 South Battery and on the Elliott family plantation at Rantowles.

1758

A “New Barracks” of pine-timber was constructed for British soldiers on what is now the site of the College of Charleston. Lt. Col. Bouquet again demanded that the Assembly pay the officers’ rents in private homes. The legislature refused, claiming that the traditional right of Englishmen to be free of quartering soldiers was being violated.

1774

The South Carolina Gazette reported of “a most infamous and dangerous Set of Villains, of whom the Public had entertained very little Suspicion.” Two slaves were arrested as “Principals” in “several of the Burglaries and Robberies, which had been so frequent of late.” After questioning the slaves, authorities also arrested “John Thomson, an Umbrella-maker and Shop-keeper, Richard Thomson, who kept a Livery Stable, and George Vargent, a Coachman.”

The two slaves received a death sentence and were hanged a few days later. The three white men were sentenced to sit twice in the pillory where they were “most severely pelted,” given a whipping of thirty-nine lashes each, and fine from 25 to 500 pounds.