Stephen Sondheim in Invisible Giants: Fifty Americans Who Shaped the Nation But Missed the History Books, wrote:

DuBose Heyward has gone largely unrecognized as the author of the finest set of lyrics in the history of the American musical theater – namely, those of Porgy and Bess. There are two reasons for this, and they are connected. First, he was primarily a poet and novelist, and his only song lyrics were those that he wrote for Porgy. Second, some of them were written in collaboration with Ira Gershwin, a full-time lyricist, whose reputation in the musical theater was firmly established before the opera was written. But most of the lyrics in Porgy – and all of the distinguished ones – are by Heyward. I admire his theater songs for their deeply felt poetic style and their insight into character. It’s a pity he didn’t write any others. His work is sung, but he is unsung.

In 1922 a petition was sent to Charleston City Council, signed by thirty-seven white residents of Church Street and St. Michael’s Alley, which called for the immediate eviction of all the black residents of Cabbage Row. The petition detailed their unsavory behavior which included fornication between of black women and white sailors, knife and gun fights, unsanitary conditions and “the most vile, filthy and offensive language.”

During the spring of 1924, DuBose Heyward, founding member of the Poetry Society of South Carolina, began to work on “a novel of contemporary Charleston.” Heyward was the descendant of Thomas Heyward Jr., a signer of the Declaration of Independence. He was part of Charleston’s aristocratic heritage where family bloodlines were more important than bank accounts.

During the early 1920s DuBose Heyward gained a reputation in American literary circles as a talented, serious poet. Charleston society was rightly proud of his success and reputation. The perception at Charleston tea parties was that his forthcoming novel of “contemporary Charleston” would, of course, be a drawing room drama, or a comedy of manners. Everyone was anxious to read it, assuming it would be about “them.” They could have never imagined what Heyward actually wrote, a lyrical folk novel about the Gullahs of Charleston.

For many white Charlestonians, the ubiquitous presence of Gullahs was as common as the humidity, present but rarely acknowledged. Heyward lived on Church Street, a dignified colonial-era neighborhood that had become quite ungentrified after Emancipation. Whites descended from the elite families of Charleston society now lived in close quarters, side-by-side, with descendants of their former slaves. The once pristine houses and gardens were now covered in shabbiness, the result of decades of dwindling fortunes and cultural depression.

Heyward became fascinated by the odd story of Samuel Smalls. The Charleston News and Courier featured a small item on the police blotter:

Samuel Smalls, who is a cripple and is familiar to King Street, with his goat and cart, was held for the June term of Court of Sessions on an aggravated assault charge. It is alleged that on Saturday night he attempted to shoot Maggie Barnes at number four Romney Street. His shots went wide of the mark. Smalls was up on a similar charge some months ago and was given a suspended sentence. Smalls had attempted to escape in his wagon and was run down and captured by the police guard.

Heyward finished the first draft of a novel based on Smalls’s life. He gave the manuscript to his friend John Bennett to read. Bennett was astonished by the story. “There had never been anything like it,” he said.

The story was set in a location Heyward called “Catfish Row,” two run-down tenement buildings one block from his home on Church Street. Nestled between the two tenements was 87 Church Street, a classic brick Georgian double house that had been the home of his ancestor, Thomas Heyward, Jr. As previously noted, by the turn of the 20th century both tenements were notorious as dens of crime and violence.

85-91 Church Street, circa 1910. These pre-Revolutionary structures had deteriorated into slums by the turn of the 20th century. (L-R) Cabbage Row; Thomas Heyward House; Catfish Row. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

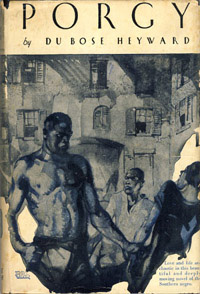

DuBose Heyward’s novel, published in September 1925, was titled Porgy. It was the story of a crippled beggar on the streets of Charleston. During a dice game, Porgy witnesses a murder committed by a rough, sadistic black man named Crown, who runs away from the police. During the next weeks, Porgy shelters the murderer’s woman, the haunted Bess, in the rear courtyard of Catfish Row, a rundown tenement on the Charleston waterfront. Porgy and Bess fall in love. However, when Crown arrives to take Bess back Porgy kills him. He is taken in by police for questioning. After ten days he is released, because the police do not believe a crippled beggar could have killed the powerful Crown. When Porgy returns to the Row, he discovers that Bess had fallen under the spell of the drug dealer Sportin’ Life and his “happy dus’.” She has followed Sportin’ Life to a new future in Savannah and Porgy is left alone, brokenhearted.

The novel became a national best-seller, and received rave reviews. DuBose Heyward was praised for portraying “Negro life more colorful and spirited and vital than that of the white community” and for creating a character that is “a real Negro, not a black-faced white man,” who “thinks as a Negro, feels as a Negro, lives as a Negro.”

In Charleston, the reaction was polite but less positive. Some acknowledged the truth: it was a powerful book. Others claimed “the paper was wasted on which it was writ.” Most people were disappointed and shocked, when they discovered Porgy’s main characters were black, not white. The white characters were little more than poorly drawn caricatures.

Lost amidst the initial praise and criticism, that, at its heart, Porgy, is a reminiscence of the old way of life in Charleston. Blacks are second class citizens, living lives of limited freedom and still expected to be subservient to whites. Porgy, however, examines this world from a black viewpoint. Portrayed with realism, these Charleston blacks were far removed from the “new Negro,” who could be seen daily on the streets of Harlem, and appearing in the literature of New York writers. In Charleston blacks and whites suffered from the same malaise.

In 1924 George Gershwin’s musical, Lady Be Good! ran for 330 performances on Broadway, establishing him as one of the most popular songwriters in America. While his second hit show, Tip-Toes, was on Broadway, Gershwin read Porgy in one sitting. He immediately wrote to Heyward proposing the two men collaborate together on an opera based on the story.

Heyward was astonished, and then excited. Gershwin was one of the most powerful, successful and talented artists in the New York musical world. He contacted Gershwin and was told that, although the composer wanted to create an opera his work schedule was booked solid for the next several years. Heyward decided to go ahead and write a nonmusical stage version of Porgy.

DuBose Heyward’s wife, Dorothy, was an award-winning playwright. The two had met in 1922 at the MacDowell Colony, an artist retreat in New Hampshire, and Heyward was immediately smitten. In 1923 they married in New York where Dorothy’s play, Nancy Ann, won Harvard’s Belmont Prize, beating out Thomas Wolfe’s Welcome to My City. First prize was $500 and a Broadway production of the play. Meanwhile, MacMillan Publishing had accepted a volume of Heyward’s poetry for publication. The young couple spent the first months of their marriage living apart, Dorothy in New York working on the play production and Heyward on a speaking tour across the South.

Heyward’s decision to go ahead with a dramatic stage version of Porgy, instead of waiting for Gershwin, was an important one. After all, he already had the perfect collaborator living under the same roof. Together the Heywards turned the novel into a stage play. Gershwin was fully supportive of the effort. He told Heyward that a stage script of the story could more easily be transformed into a libretto for the proposed opera.

Dorothy wrote most of the dialogue for the play, smoothing the Gullah dialect from the novel into more recognizable English. By the summer of 1926 the play was written and submitted to three professional production companies in New York. One week later, it was accepted by the Theatre Guild, but the Heywards were pessimistic that the play would ever be produced. They had one unshakable demand, which could easily have been the death knell of the production; they wanted black actors to play the black roles, not white actors in blackface, still common at the time. The original director resigned due to their demands and the play was set aside.

In early 1927 a young Armenian director named Rouben Mamoulian decided he would direct Porgy, with a black cast. Trained as a lawyer, Mamoulian and his sister had fled Russia during the Bolshevik Revolution, moved to London and began working in West End theaters. Mamoulian arrived in America at the invitation of George Eastman (of Eastman-Kodak) to work for the American Opera Company. It was there that he attracted the attention of the Theatre Guild, who asked him to stage Porgy.

Over the next thirty years, Mamoulian came to be known as “the mad Armenian” due to his frenetic energy. He directed more than twenty Hollywood movies and several successful Broadway plays, including the original Oklahoma (1943) and Carousel (1945). Porgy, however, was to be his first opportunity in charge of a Broadway production.

Rouben Mamoulian

To prepare, Mamoulian traveled to Charleston to soak up the atmosphere and learn about the Gullah culture. On his second day in Charleston, he was taken to the Jenkins Orphanage for an after-dinner private concert. Several women sang spirituals and then members of the Jenkins Band performed. Mamoulian was amazed by the band’s “melodious discordance” and the “infinitesimally small darkey boy who led the band.” Before leaving Charleston the next day, he persuaded Rev. Daniel Jenkins to allow the band to appear in the Porgy production.

Opening night for Porgy was October 10, 1927. At the beginning of the second act, when the cast travels to Kittawah Island for the picnic, they were led onstage by the Jenkins Band playing “Sons and Daughters Repent Ye Saith the Lord.”

Within a week, Porgy was playing to standing-room-only audiences. When it closed after 367 performances it was viewed as an overwhelming success, with a higher box office than its main competitor, Eugene O’Neill’s All God’s Chillun Got Wings. During its run Porgy employed more than sixty black performers in a serious drama, unheard of on Broadway at that time.

Five years later, George Gershwin’s heavy work schedule finally lightened enough to allow him to devote his energies to the opera. In late February 1934 he reported to Heyward that “I have begun composing music for the first act, and I am starting with the songs and spirituals first.” He then asked Heyward to join him in New York so the work could be expedited. Over the next two months, while living in a guest suite at Gershwin’s famous fourteen-room house at 132 East Seventy-second Street, Heyward wrote the lyrics for almost a dozen Gershwin compositions, including “Summertime,” “A Woman Is a Sometime Thing,” “Buzzard Song,” “It Take A Long Pull to Get There,” “My Man’s Gone,” “It Ain’t Necessarily So” and “I Got Plenty of Nuttin’.” The opera was beginning to take shape.

In June 1934, George Gershwin arrived by train in Charleston with his cousin, artist Henry Botkin. They drove out to Folly Beach, where Heyward had rented a cottage at 708 West Arctic Avenue.

Folly Beach was a remote, sparsely developed barrier island ten miles from Charleston. It was a vastly different world from Gershwin’s New York neighborhood, in the middle of rollicking night life and luxurious accommodations. Life at Folly Beach was at best simple and at worst primitive. The surrounding marshes were filled with gators and other wild, exotic creatures. Crabs and snakes entered houses freely. Heat and humidity often reached equatorial proportions. In his letters Gershwin complained that the heat “brought out the flys, and knats, and mosquitos,” leaving “nothing to do but scratch.” Two weeks later, the Herald-Journal (Spartanburg, S.C.) filed this story:

GERSHWIN, GONE NATIVE, BASKS AT FOLLY BEACH

Charleston, June 30.

Bare and black above the waist, an inch of hair bristling from his face, and with a pair of tattered knickers furnishing a sole connected link with civilization, George Gershwin, composer of jazz music, had gone native. He is staying at the Charles T. Tamsberg cottage at Folly Beach, South Carolina.

“I have become acclimated,” he said yesterday as he ran his hand experimentally through a crop of dark, matted hair which had not had the benefit of being combed for many, many days. “You know, it’s so pleasant here that it’s really a shame to work.”

Two weeks at Folly have made a different Gershwin from the almost sleek creator of “Rhapsody in Blue” and “Concerto in F” who arrived from New York City on June 16. Naturally brown, he is now black. Naturally sturdy, he is now sturdier. Gershwin, it would seem intends to play the part of Crown, the tremendous buck in “Porgy” who lunges a knife into the throat of a friend too lucky at craps and who makes women love him by placing huge black hands about their throats and tensing their muscles.

The opera “Porgy” which Gershwin is writing from the book and play by DuBose Heyward, is to be a serious musical work to be presented by the Guild Theater early next year, is an interpretation in sound of the life in Charleston’ “Catfish Row”; an impressionistic dissertation on the philosophy of negro life and the relationship between the negro and the white. Mr. Heyward, who is staying at Lester Karow’s cottage at the beach, spends every afternoon with the composer, cutting the score, rewriting and whipping the now-completed first act into final form.

“We are attempting to have an opera that is serious and dramatic,” Mr. Gershwin said. “The whites will speak their lines, but the negroes will sing throughout. I hope the audience will get the idea. With the colored people there is always a song, see? They always find something to sing about somewhere. The whites are dull and drab.”

It is the crap game scene and subsequent murder by Crown which may make the first act the most dramatic of the production. A strange rhythm and an acid, biting quality in the music create the sensation of conflict and strife between men and strife caused by the rolling bones of luck.

“You won’t hear the dice click and roll,” he said. “It is impressionism, not realism. When you want to get a great painting of nature you don’t take a camera with you.”

Jazz will rear its hotcha head at intervals through the more serious music. Sporting Life, the negro who peddles “joy powder” or dope, to the residents of Catfish Row, will be represented by ragtime.

“Even though we are cutting as much as possible, it is going to be a very long opera,” Mr. Gershwin said. “It takes three times as long to sing a line as it does to say it. In the first act, scene one is 94 pages of music long and scene two is 74.”

There is only one thing about Charleston and Folly that Mr. Gershwin does not like. “Your amateur composers bring me their pieces for me to play. I am very busy and most of them are very bad – very, very bad,” he said.

Heyward took Gershwin on forays to neighboring James Island, which had a large Gullah population. They visited schools and especially churches. Gershwin was particularly fascinated by a dance technique called “shouting,” which entailed beating out a complicated rhythm with the feet and hands to accompany the spiritual singing. Heyward wrote:

The most interesting discovery to me, as we sat listening to their spirituals …was that to George it was more like a homecoming than an exploration. The quality in him which had produced the “Rhapsody in Blue” in the most sophisticated city in America, found its counterpart in the impulse behind the music and bodily rhythms of the simple Negro peasant of the South.

I shall never forget the night when at a Negro meeting on a remote sea-island George started ‘shouting’ with them. And eventually to their huge delight stole the show from their champion ‘shouter.’ I think he is probably the only white man in America who could have done it.

The first version of the opera ran four hours, with two intermissions, and was performed privately in a concert version at Carnegie Hall in 1935. The world premiere took place at the Colonial Theatre in Boston on September 30, 1935, the traditional out-of-town performance for any show headed for Broadway. The New York opening took place at the Alvin Theatre on October 10, 1935 and ran for 124 performances, impressive for an opera but woefully short for a musical. The reviews were decidedly mixed.

Brooks Atkinson wrote in the New York Times, October 9, 1935:

After eight years of savory memories, Porgy has acquired a score, a band, a choir of singers and a new title, Porgy and Bess, which the Theatre Guild put on at the Alvin last evening … Although Mr. Heyward is the author of the libretto and shares with Ira Gershwin the credit for the lyrics, and although Mr. Mamoulian has again mounted the director’s box, the evening is unmistakably George Gershwin’s personal holiday … Let it be said at once that Mr. Gershwin has contributed something glorious to the spirit of the Heywards’ community legend.

It was called “crooked folklore and halfway opera” by Virgil Thomson. Whereas, Lawrence Levine stated: “Porgy and Bess reflects the odyssey of the African American in American culture.” Most critics complained about the form of the show – was it opera or musical?

Gershwin himself anticipated those reactions. In the New York Times in 1935 he said:

Because Porgy and Bess deals with Negro Life in America it brings to the operatic form elements that have never before appeared in the opera and I have adapted my method to utilize the drama, the humor, the superstition, the religious fervor, the dancing and the irrepressible high spirits of the race. If doing this, I have created a new form, which combines opera with theater, this new form has come quite naturally out of the material.

The argument still rages.

George Gershwin and Dubose Heyward on Chalmers Street, Charleston.

People in Charleston, however, wasted little time in taking advantage of Porgy and Bess for profit. As the first American folk opera, composed by one of America’s greatest composers and based on a story written by a native son, the opera was a boon for Charleston marketing. Loutrel Briggs, landscape architect, who had moved to Charleston, became the driving force behind a movement to clean up Cabbage Row. He wanted to save the Row. He wrote:

DuBose Heyward, with an artistry to which my unskilled pen cannot do justice, has preserved for posterity the picturesque life of “Catfish Row,” and I have attempted to reclaim, with as little external change as possible, this building and restore it to something of its original state in revolutionary time.

The Chamber of Commerce paid for the placement of historical markers on structures throughout the city. The 1929 opening of the Cooper River Bridge had given motorists direct access to the city via Route 40 and the Atlantic Coast Highway. There was already an increase of tourists visiting in the city.

The Chicago Tribune wrote:

In a world of change, Charleston changes less than anything …. Serene and aloof, and above all permanent, it remains a wistful reminder of a civilization that elsewhere has vanished from earth.

With the Great Depression gripping America, Charleston was in no financial position to turn away money. The pre-Revolutionary residential area of Heyward’s former neighborhood – Church and Tradd Streets – became a haven for tourist shops, catering to the much-disdained but much-needed Yankee dollar. Ladies of “quality” from Charleston’s “first families” opened coffee houses and tea shops and served as “lady guides” on walking tours down the cobblestone streets and back alleys. Their version of Charleston was completely focused on the glory days of the past, discussing “servants” not slaves, architecture not secession, George Washington not Jim Crow. They were trying to preserve, or more realistically, resurrect what Rhett Butler described in Gone With The Wind: “the calm dignity life can have when it’s lived by gentle folks, the genial grace of days that are gone.”

Led by two community-boosting-mayors John P. Grace and Thomas Stoney, this refocusing of history transformed Charleston in the 20st century. The 1930s preservation and tourism campaign solidified Charleston’s image as “America’s Most Historic City,” making it the darling of upscale tourists. In 2012, readers of the international travel magazine Conde Nast Traveler voted Charleston the #1 Tourism City in the World.

Broadway production of Porgy & Bess. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Kendra Hamilton wrote:

The ironies of the situation are compelling. Charleston becomes daily more segregated, the chasm between rich and poor ever deeper and wider, as in the salad days before the war. The tourist-minded city fathers become daily more ingenious at smoothing down the ugly truths of the city’s history so as to increase its appeal to people whose impressions of the South owe more to Scarlett O’Hara than Shelby Foote. And yet, the city’s most readily identifiable cultural emblems – from Porgy to “the Charleston” – have African-American roots.

During the 1930s and ‘40s, DuBose Heyward’s former home at 76 Church Street became the Porgy Shop. This store sold antiques, china curios and other fine furnishings that had nothing to do with the opera, the play or the novel. It certainly had nothing in common with its namesake, a poor, violent, black beggar turned folk hero.

Porgy House. Dubose Heyward’s home on Church Street where he wrote the novel Porgy, was turned into a gift shop.

In another ironic twist, the “first families” of Charleston, who made money from this skewed, picturesque version of history, did not even allow a version of their most famous commodity to be performed in its home setting until 1970, thirty-four years after its debut. Indeed, Charleston often goes out of its way to soften its African history. In the 1991 video, Charleston, S.C.: A Magical History Tour, Mrs. Betty Hamilton, daughter of artist Elizabeth O’Neill Verner, discusses her mother’s 1920s-era paintings as capturing “the Gullah South Carolina niggra with their simplicity and their sweetness.”

In 1952 a new international production of Porgy and Bess was mounted, featuring twenty-four year old newcomer Leontyne Price as Bess and the veteran Cotton Club song-and-dance man Cab Calloway as Sportin’ Life. This production was a theatrical triumph in Vienna, Berlin and London and also a hit when it returned to New York’s Ziegfeld Theater. The black press, however, launched a furious attack on the opera. James Hicks, a reporter with the Baltimore Afro-American, called the opera:

the most insulting, the most libelous, the most degrading act that could possibly be perpetrated against colored Americans of modern times.

Critic William Warfield noted:

In 1952 the black community wasn’t listening to anything about plenty of nothing being good enough for me. Blacks began talking about being black and proud.

In 1954 there was an effort to produce Porgy in Charleston, but it ran into trouble. South Carolina law at the time forbade the “mixing of the two races in places of amusement” for “historic reasons of incompatibility.” Local black performers refused to perform in front of a segregated audience and the show was canceled. It wasn’t until 1970, during South Carolina’s tri-centennial festivities that an amateur production of Porgy and Bess was approved and subsequently performed in Charleston before an integrated audience. It was the first amateur production of the opera allowed by the Gershwin estate, but by that time, the opera had acquired a problematic legacy.

During the 1960s the Civil Rights and black power movements transformed America. Porgy and Bess became an embarrassment to many black activists. Harold Cruse wrote that:

Porgy and Bess belongs in a museum and no self-respecting African American should want to see it, or be seen in it.

Such is the love-hate relationship associated with Porgy and Bess, and the ebb-and-flow of cultural acceptance that endures to this day. However, in 2011 the story was reborn for Broadway. Titled The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess and starring four-time, Tony-award winner Audra MacDonald, the new show was not without its own controversy. The producers changed some of the story and music to make it more appealing to modern audiences. The operatic-styled recitatives were replaced by spoken dialogue.

Nonetheless, the production was a runaway hit. It received ten nominations at the 2012 Tony Awards, winning Best Revival of a Musical and Best Performance by a Leading Actress in a Musical for McDonald. It played for 322 performances, seventeen more than the 1953 revival, making it the longest-running production of Porgy and Bess on Broadway.

This year, 2016, Porgy & Bess is being performed during the Spoleto Festival in Charleston, and is accompanied by an all-out effusive campaign that encompasses the entire city and every media outlet – 81 years later.