1739

The South Carolina Gazette announced festivities to honor James Oglethorpe:

Tuesday last being the day appointed for the Review of the Troop and Regiment of St. Philips Charlestown, the two following commissions of his Majesty were published at Granville Bastion, under the discharge of the cannon both there and at Broughton Battery the one constituting and appointing the Hon. William Bull Lieutenant Governor in and over the province, and the other [for] his Excellency James Oglethorpe, General and Commanders of his Majesty’s Forces in the provinces of South Carolina and Georgia … In the evening his Excellency … made a general invitation to the ladies to an excellent supper and ball so the day concluded with much pleasure and satisfaction.

1740 – Slavery

Stono Rebellion

In response to the Stono Rebellion, the Assembly passed a new Negro Act – placing high import duty on slaves, which effectively cut off new slave trading. Its stated goal was “to ensure that slaves be kept in due subjection and obedience.”

No slave living in town was allowed to go beyond the city limits; the sale to alcohol was prohibited and teaching slaves to read and write was prohibited. Only the Assembly could grant a slave freedom. Any white person who “shall willfully cut out the tongue, put out the eye, castrate or cruelly scald” a slave was subject to a fine.

1765 – American Revolution–The Sugar Act

The Sugar Act was passed by Parliament. The British government had increased its debt during the French and Indian War, and was looking at various means to raise revenue.

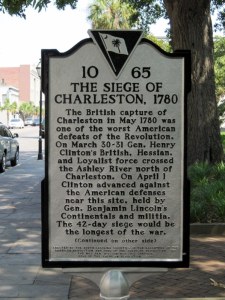

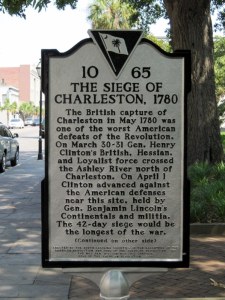

1780 – The Siege of Charlestown

Siege of Charlestown – British batteries outside the city.

After dark Gen. Clinton ordered the British battery at Fenwick’s Point and the Wappoo Cut, across the Ashley River, to fire upon Charlestown. The cannonballs whistling through the dark sky over the city created a “terrible clamor” with “the loud wailing of female voices.”

One of the British cannonballs struck Mr. Thomas Elfe’s house at 54 Queen Street and two damaged Governor John Rutledge’s house on Broad Street. Rutledge wrote that he was appalled at “the insulting Manner in which the Enemy’s Gallies have fired, with Impunity, on the Town.”

Also, the British galley Scourge fired eighty-five times with “every shot … into town.” During the night three British soldiers deserted to the American side. One of the soldiers “paddled himself over on a plank from James Island.”

Siege marker on King Street @ Marion Square

1839

Robert Smalls was born behind his owner’s city house at 511 Prince Street in Beaufort, S.C. His mother, Lydia, served in the house but grew up in the fields, where, at the age of nine, she was taken from her own family on the Sea Islands. The McKee family favored Robert Smalls over the other slave children, so much so that his mother worried he would reach manhood without grasping the horrors of the institution into which he was born. To educate him, she arranged for him to be sent into the fields to work and watch slaves at “the whipping post.”

By the time Smalls turned 19, he was working in Charleston. He was allowed to keep one dollar of his wages a week (his owner took the rest). Far more valuable was the education he received on the water; few knew Charleston harbor better than Robert Smalls.

Robert Smalls

It’s where he earned his job on the Planter. It’s also where he met his wife, Hannah, a slave of the Kingman family working at a Charleston hotel. With their owners’ permission, the two moved into an apartment together and had two children: Elizabeth and Robert Jr. Well aware this was no guarantee of a permanent union, Smalls asked his wife’s owner if he could purchase his family outright; they agreed but at a steep price: $800. Smalls only had $100.

By 1862, Smalls viewed the Union blockade of the Charleston harbor as a tantalizing promise of freedom. Under orders from Secretary Gideon Welles in Washington, Navy commanders had been accepting runaways as contraband since the previous September. While Smalls couldn’t afford to buy his family on shore, he knew he could win their freedom by sea — and so he told his wife to be ready for whenever opportunity dawned.

The Planter

Just before dawn on May 13, 1862, Robert Smalls and a crew of fellow slaves, slipped a cotton steamer, Planter, off the dock, picked up family members at a rendezvous point, then slowly navigated their way through the harbor. Smalls, doubling as the captain donned the captain’s wide-brimmed straw hat to help to hide his face. As they sailed out of the harbor Smalls responded with the proper coded signals at two Confederate checkpoints and sailed into the open seas. Once outside of Confederate waters, he had his crew raise a white flag and surrendered his ship to the blockading Union fleet.

In less than four hours, Smalls had accomplished an amazing feat: commandeering a heavily armed Confederate ship and delivered its 17 black passengers (nine men, five women and three children) from slavery to freedom. “One of the most heroic and daring adventures since the war commenced was undertaken and successfully accomplished by a party of negroes in Charleston,” trumpeted the June 14, 1862, edition of Harper’s Weekly.

On May 30, 1862, the U.S. Congress, passed a private bill authorizing the Navy to appraise the Planter and award Smalls and his crew half the proceeds for “rescuing her from the enemies of the Government.” Smalls received $1,500 personally, enough to purchase his former owner’s house in Beaufort off the tax rolls following the war, though according to the later Naval Affairs Committee report, his pay should have been substantially higher.

In the North, Smalls was hailed as a hero. He lobbied Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to begin enlisting black soldiers and a few months later after President Lincoln ordered black troops raised, Smalls recruited 5,000 soldiers himself. In October 1862, he returned to the Planter as pilot as part of Admiral Du Pont’s South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. According to the 1883 Naval Affairs Committee report, Smalls was engaged in approximately 17 military actions, including the April 7, 1863, assault on Fort Sumter and the attack at Folly Island Creek, S.C.

Two months later he assumed command of the Planter when, under “very hot fire,” its white captain became so “demoralized” he hid in the “coal-bunker.” Smalls was promoted to the rank of captain, and starting in December 1863 on, he earned $150 a month, making him one of the highest paid black soldiers of the war. When the war ended in April 1865, Smalls was on board the Planter in a ceremony in Charleston Harbor at Fort Sumter.

Following the war, Smalls served in the South Carolina state assembly and senate, and for five nonconsecutive terms in the U.S. House of Representatives (1874-1886).He died in Beaufort on February 23 1915, in the same house behind which he had been born a slave and is buried behind a bust at the Tabernacle Baptist Church.

“My race needs no special defense for the past history of them and this country. It proves them to be equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.” — Robert Smalls