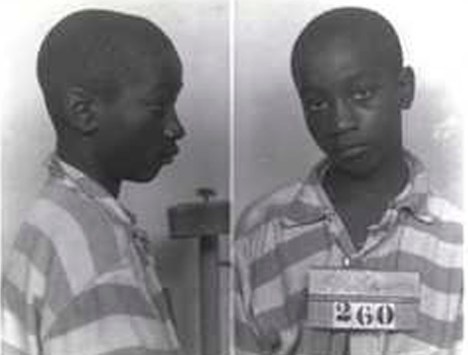

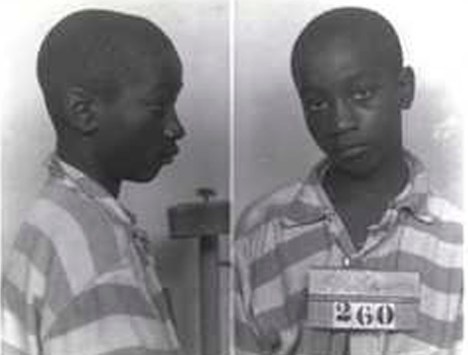

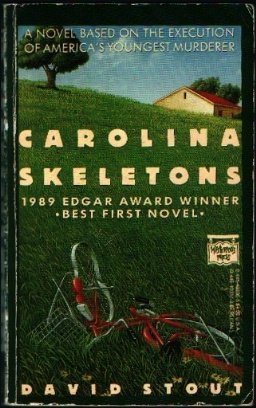

This is the sad saga of the youngest person ever executed in the United States. It was the inspiration for the 1989 Edgar Award–winning book for Best First Novel, Carolina Skeletons, by David Stout. The book became the basis for the 1992 movie of the same name starring Lou Gossett Jr. and Bruce Dern.

Recently a judge vacated Stinney’s conviction – 70 years too late. For those unfamiliar with the story, here is my version from my 2007 book, South Carolina Killers: Crimes of Passion.

1944

Clarendon County, South Carolina can claim to be the home of some notable Americans. Althea Gibson, the first African American woman to play tennis at Wimbledon, Peggy Parish, author of the famous Amelia Bedelia children’s books, and the birthplace to five South Carolina governors. It was also the location of the small town of Alcolu where most of the residents, black and white, worked at the Alderman Lumber Company Mill, were farmers or both.

In 1944, most people in the tiny mill town were just trying to get by and hoping the few local boys who were serving in the war would make it back home. The most recent American casualty totals for World War II had just recently been released—19,499 killed, 45,545 wounded, 26,339 missing and 26,754 captured. Every day the newspaper was filled with death tolls and descriptions of war horrors, and though no one knew it, the worst was yet to come. The D-Day invasion of Normandy was two and a half months away.

March 24, 1944.

Betty June Binnicker, age eleven, and Mary Emma Thames, age eight, went to pick flowers that afternoon. Betty June asked permission to take a pair of scissors and then told her family, “We’ll be back in about thirty minutes.” The girls rode off together on one bicycle. No one was concerned. The girls often played on this side of town, and several people saw the familiar scene of the two girls riding double. They passed by the Stinney house. Even though the Stinneys were black, both girls knew the Stinney kids. Katherine Stinney and her older brother, George Jr., were in the front yard. “We’re looking for maypops,” Betty June said. “Do you know where they are?”

Katherine told them no, and the two girls rode off on their bikes.

When the two girls didn’t return by dark, the Binnicker family was panicked. Soon a town-wide search was launched, with hundreds of volunteers. They searched through the entire night. About 7:30 a.m. the next morning, some men found several small footprints in the soft ground and followed the footprints along a narrow path on the edge of town, where they found the pair of scissors lying in the grass nearby. Following the path with more urgency, the searchers discovered a large ditch filled with muddy water. They could see the outline of a bicycle beneath the murky surface. Scott Lowden jumped into the water, and the bodies of the two girls were dragged out. Both girls had severe head wounds—Mary Emma’s skull was fractured in five different places and the back of Betty June’s skull was smashed.

Within a few hours, local sheriff’s deputies arrested George Stinney Jr. His youngest sister, Katherine Stinney Robinson, later recalled, “And all I remember is the people coming to our house and taking my brother. And no police officers with hats or anything—these were men in suits or whatever that came. I don’t know how they knew to come to that house and pick up my brother.”

George was taken to the sheriff’s office, where he was interrogated. In 1944, there were no Miranda rights to be read to the accused. George was locked in a room with several white officers. Neither of George’s parents were allowed to see him. Within an hour, Deputy H.S. Newman announced that Stinney had confessed to the murders. Stinney told police that he wanted to have sex with Betty June, but the only way to get her alone was to get rid of Mary Emma. But Betty June fought him, so he killed her too. Stinney then led the police to the scene, where they found a fourteen-inch-long railroad spike. Deputy Newman wrote a statement on March 26, 1944, and described the events.

I was notified that the bodies had been found. I went down to where the bodies were at. I found Mary Emma she was rite [sic] at the edge of the ditch with four or five wounds on her head, on the other side of the ditch the Binnicker girl, were [sic] laying there with 4 or 5 wounds in her head, the bicycle which the little girls had were beside of the little Binnicker girl. By information I received I arrested a boy by the name of George Stinney, he then made a confession and told me where a piece of iron about 15 inches long were, he said he put it in a ditch about 6 feet from the bicycle which was lying in the ditch.

The town was horrified by the crime and overwhelmed with grief. Both girls’ parents worked at the Alderman Lumber Mill, as did Mr. George Stinney Sr. Within a few hours, the grief among the millworkers had quickly transformed into a seething anger.

March 26, 1944.

About forty angry white men headed for the Clarendon County Jail and demanded mob justice, but sheriff’s deputies were one step ahead of the folks. They had moved Stinney fifty miles away to Columbia.

B.G. Alderman, owner of Alderman’s Lumber Mill, fired George’s father. The Stinney family lived in such fear for their lives that they moved from town in the middle of the night, abandoning their son to his fate.

George Stinney Jr. was fourteen years, five months old when he went on trial. The first recorded execution of a juvenile in America was Thomas Graungery, age sixteen, of Plymouth Rock, Massachusetts, who was hanged for bestiality. On March 14, 1794, two young slave girls, “Bett, age 12” and “Dean, age 14,” were executed for starting a fire that burned down a portion of Albany, New York. In 1988, the U.S. Supreme Court passed a ruling that “prohibits the death penalty for juvenile offenders whose crimes were committed before they were 16.” Prior to 1988, there was no age limit for executions.

Lorraine Binniker Bailey was Betty June’s older sister. She recalled that “everybody knew that he done it—even before they had the trial they knew he done it. But, I don’t think they had too much of a trial.”

Katherine Stinney Robinson later recalled, “I remember my mother cried so. She cried her little eyes all swollen. I would hear her praying. She said, ‘I just want you to change the minds of men. Because my son didn’t do this.’ But it wasn’t long after that that they just did it. He was gone.”

The court appointed thirty-year-old Charles Plowden as George’s attorney. Plowden had political aspirations, and the trial was a high-wire act for him. His dilemma was how to provide enough defense so that he could not be accused of incompetence, but not be so passionate that he would anger the local whites who may one day vote for him.

April 24, 1944.

More than 1,500 people crammed into the Clarendon County Courthouse. Jury selection began at 10:00 a.m. and was finished just after noon. The jury contained twelve white men. Due to the nature of the crime and the passion of the community, it certainly would have been in George Stinney’s favor to have a change in venue. But defense attorney Plowden made no motion.

After a lunch break, the case was heard before Judge Stoll. Plowden did not cross-examine any of the prosecuting witnesses. His defense consisted of claiming that Stinney was too young to be held responsible for the crimes by law. In response, the prosecution presented Stinney’s birth certificate stating that he was born on October 21, 1959, which made him fourteen years and five months old. Under South Carolina law in 1944, an adult was anyone over the age of fourteen.

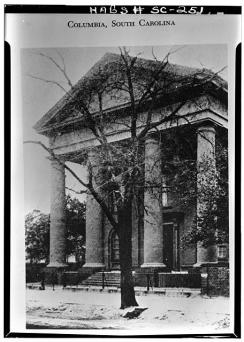

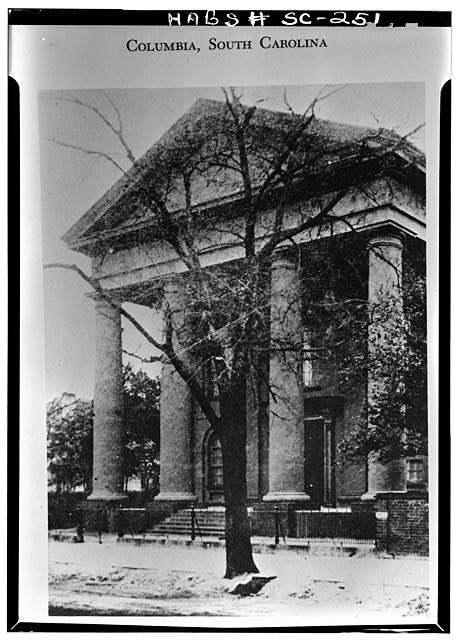

The case had begun at 2:30 p.m. and closing arguments were finished by 4:30. The jury retired just before 5:00 p.m. and deliberated for ten minutes. They returned with the verdict “guilty, with no recommendation for mercy.” The case took less than three hours to decide. Judge Stoll sentenced Stinney to die in the electric chair at the Central Correctional Institute in Columbia.

When asked about an appeal, Defense Attorney Plowden stated that there was nothing to appeal and the Stinney family had no money to pay for a continuance of the case.

Several local churches, in conjunction with the NAACCP, appealed to Governor Olin D. Johnston to stop the execution. The governor’s office received letters for mercy. Most cited Stinney’s age as the mitigating factor why the execution should be dropped. One message was as direct as could be in 1944 by stating “child execution is only for Hitler.” The Tobacco Worker’s Union, the National Maritime Union and the White and Negro Ministerial Unions of Charleston asked Governor Johnston to commute the sentence to life imprisonment.

However, there were just as many, if not more, in favor of the execution who encouraged the governor to be strong. One of the more blunt letters to the governor stated, “Sure glad to hear of your decision regarding the nigger Stinney.”

The governor decided to do nothing. He let the execution proceed.

June 16, 1944.

At 7:30 p.m., George Stinney Jr. was fitted into the electric chair. It had been designed for grown men, not children. He was five feet, one inch tall and weighed ninety pounds. The guards had a hard time strapping him into the seat. The mask over his face did not fit properly. When the switch was thrown, the force of the electricity jerked the too-large mask from his face, and for the final four minutes of his life, the spectators in the gallery had a full view of Stinney’s horrified face as he was executed.

Stinney’s sister, Katherine Stinney Robinson, was interviewed on the fiftieth anniversary of her brother’s execution and said

He was like my idol, you know. He was very smart in school, very artistic. He could draw all kinds of things. We had a good family. Small house, but there was a lot of love. It took my mother a long time to get over it. And maybe she never got over it.

The time span of the entire episode, from the girls’ death to Stinney’s execution, was eighty-one days.

Novel based on the Stinney case.