Why were the South Carolina gentry more extreme, and more obstinate than other Southerners?

The Colony of a Colony. Unlike most earlier colonists to Virginia and Chesapeake, many early Carolina settlers came not from England, but from Barbados, an important distinction. During the English Civil War (1642-51) Barbados became an asylum for Royalists seeking to avoid the conflict, and the violent Puritanism of Oliver Cromwell. After the 1649 execution of Charles I, Parliament sought to punish Barbados for their loyalty to the monarchy by restricting their trade, creating an economic crisis for the small island. To sustain their economy, Barbadians began to rely on trade with the Dutch Republic, until Cromwell and Parliament passed the Navigation Act of 1651, which banned the use of non-English ships to carry English goods. This essentially prohibited all trade with the Dutch, but Barbadian merchants carried on illicit privateering until England invaded the island and the Royalist Barbadian House of Assembly surrendered. The Carolina colony would soon become the “promised land” for many Barbadian merchants and planters.

In March 1663, Charles II granted the territory called Carolana to the “true and absolute Lords and Proprietors,” eight men who had been instrumental in restoring him to the throne after Cromwell’s death. There was a strong consensus among the Proprietors that the colony could be more easily, and inexpensively, developed luring experienced settlers from established Caribbean colonies by offering large grants in lieu of providing financing. Three months later, John Colleton of Barbados informed the Lord Proprietors that “many citizens were interested in moving to Carolina.” The Colleton family gathered two hundred “Barbadian Adventurers” and engaged Captain William Hilton to explore the Carolina coast to search for suitable settlement sites. Each member of the “Adventurers” was entitled to five hundred Carolina acres for every 1,000 pounds of sugar contributed.

The Proprietors also adopted the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina, that, they hoped, would establish a “perfect government.” The Constitutions were “a grand and impractical political framework … that envisioned an orderly, quasi-feudal system under their immediate control.” Although never formally adopted, the Constitutions did become the working blueprint for settling and governing the new colony. It offered “religious freedom for anyone who believed in God”, established the Church of England as the tax-supported religion, and forbade Catholicism. It also created a system of government by the landed gentry. To vote a man must own fifty acres and to hold a seat in the Assembly, he must own five hundred. All “free settlers over the age of sixteen” were promised 150 acres, and an additional 100 for every able-bodied servant.” Servants could include family members and “indentured servants”. Every individual that acquired 3,000 acres “would have all the rights of a lord of the manor established by English law.” The Proprietors forbid the enslavement of the local Natives in Carolina but set out specific and strict laws for African slavery, based on the Barbadian system which declared “Every freeman of Carolina shall have absolute power and authority over his negro slaves.”

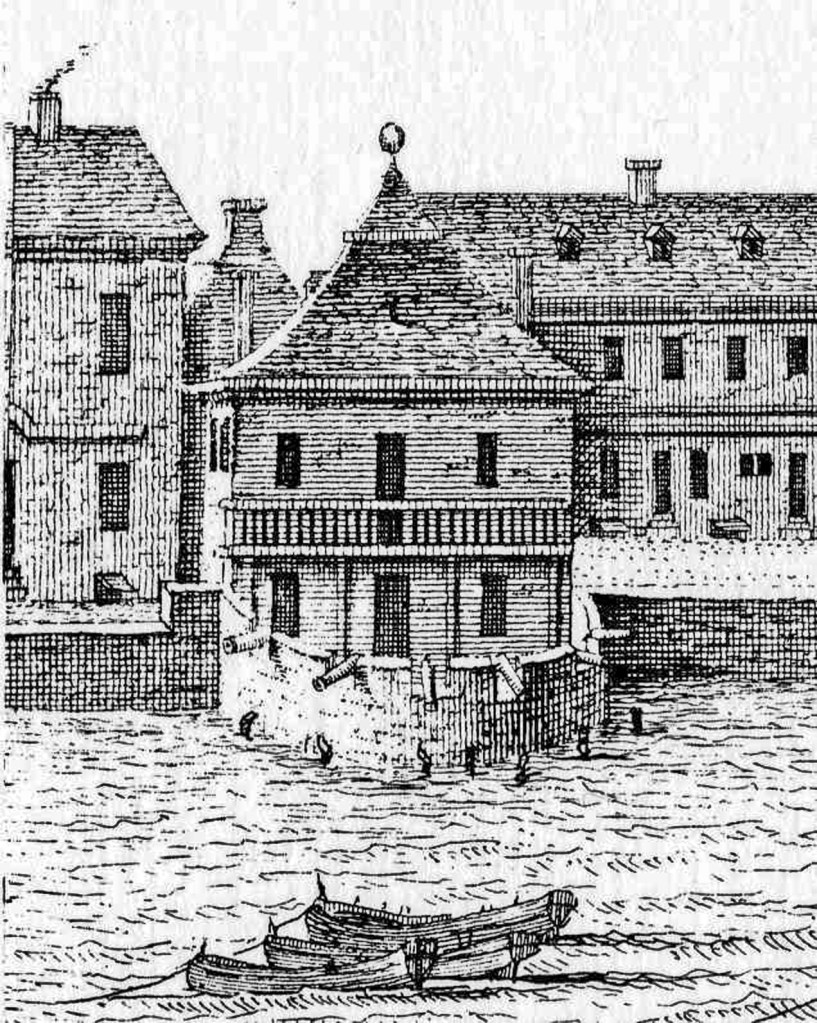

In April 1670, the first English settlement south of Virginia was established in Carolina, called Charles Town. Barbadians cast a long shadow and influenced much of the life in Charles Town, establishing the model for what became romanticized as “the Old South.” They lived with “a combination of old-world elegance and frontier boisterousness. Ostentatious in their dress, dwellings, and furnishings, they liked hunting, guns, dogs, military titles like ‘Captain” and ‘Colonel’ … They enjoyed long hours at their favorite taverns over bowls of cold rum punch or brandy.”

They also had little interest in the Proprietors’ lofty notions of a perfect government, and quickly controlled the colony by dominating the Council and the governorship. John Coming, from England, wrote that “the Barbadians endeavor to rule all.” The Council claimed that since the Carolina charter was issued after the Navigation Act, it superseded that law and claimed that they “totally disclaimed the authority of the British Parliament in which they were not represented.” So, from the beginning of Carolina, the landed gentry were already at odds with the British authority to regulate their trade, and their lives. Their argument was that since they were governed without representation in Parliament, the Council felt within their rights to ignore the law and trade as they pleased. This would become a recurring theme in South Carolina politics for the next 200 years.

The Bloodless Revolution – Proprietors Overthrown. In 1715, the Assembly officially asked the London Board of Trade to void the Proprietor’s charter. Forty years into the life of Carolina, the Proprietors had become disenchanted with a colony that “failed to produce the great wealth and prestige they had expected.” That disappointment evolved into apathy and soon, the colonists learned to “survive with minimal assistance … from their increasingly passive proprietors.”

The fate of Proprietary Rule was sealed with two events, the devasting, and almost catastrophic Yemassee War (1715-1718), and the battle against pirates (1718-1719.) Both events “provided the colonists with galling evidence that the men in London had placed personal profit above the public welfare.”

At the end of 1719, the South Carolina Assembly convened “a convention of the people” and denounced the rule of the Lord Proprietors. They vowed “to get rid of the oppression and arbitrary dealings of the Lords Proprietors” and declared itself “the government until His Majesty’s pleasure be known.” They officially petitioned King George I to purchase the Carolina colony from the Proprietors.

Governor Robert Johnson, appointed by the Proprietors, refused to acknowledge this new government. In response the Assembly elected General James Moore Jr. as “provisional governor.” During the swearing-in ceremony Gov. Johnson arrived and ordered the militia to disperse and the illegal Assembly to desist. The militia “leveled their muskets at Governor Johnson and bid him standoff.” Johnson ultimately departed for England and for all intents and purposes, the propriety government of Carolina ended. Even though the first royal governor did not appear for eighteen months, the Provisional Government maintained power and steered the colony into a sound economy. At its heart was the concept that the revolution was to protect the “incontestable right” of Englishmen to be governed “by noe laws made here, but what are consented to by them.”

On August 11, 1720, the Lord Justices of Great Britain declared that the colony “shall be forthwith taken provisionally into the hands of the Crown.” South Carolina’s first rebellion was a polite coup d’état. They did not grab the reins of power by force, nor did they imprison their opponents. Rather, it was a “polite and passive-aggressive course of action that reflected a very British sense of honor and decorum.”