Louis Timothée, the infant son of a French Huguenot, took refuge in Holland with his family following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. In 1731, Lewis sailed onboard the Britannia from Rotterdam to Philadelphia in with his Dutch-born wife, Elizabeth, and their four small children. Shortly after his arrival in North America, he anglicized his name to Lewis Timothy, swore a loyalty oath to King George II, and placed an ad in the Pennsylvania Gazette (October 14, 1731) seeking employment. By May 1732 Lewis was working with Benjamin Franklin on the publication of the German language newspaper called the Philadelphische Zeitung. He also became a journeyman printer for the Pennsylvania Gazette and the first librarian of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

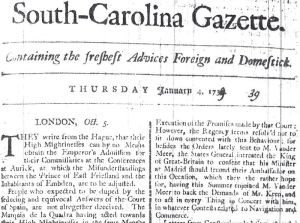

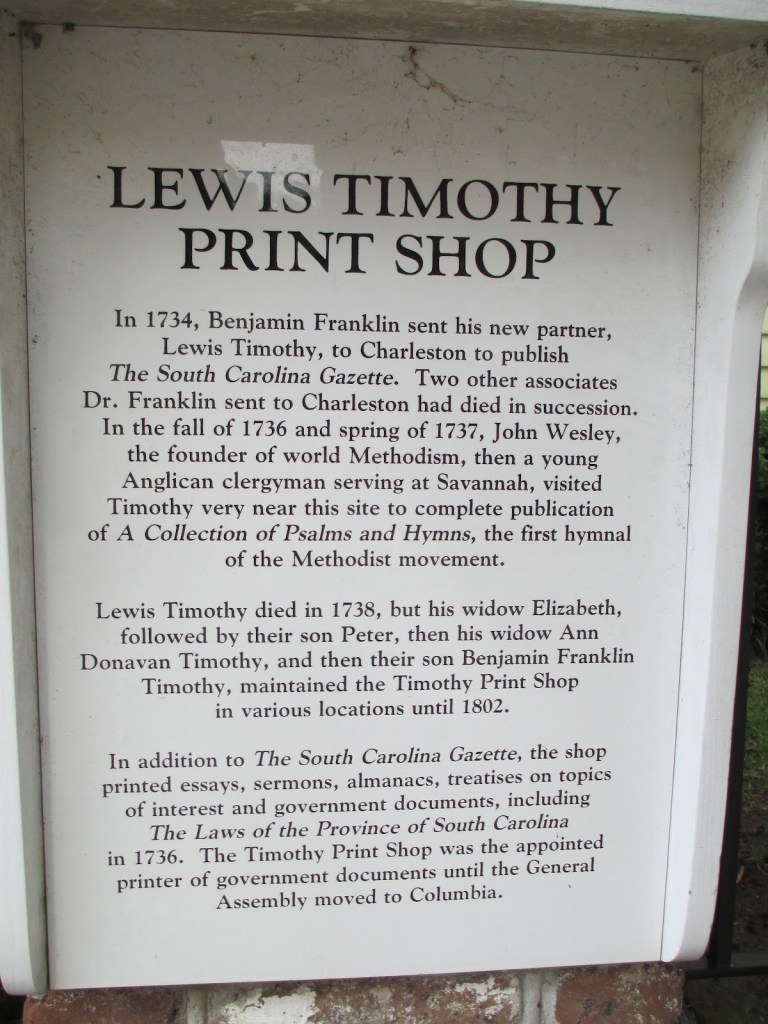

In 1733 Franklin sent Timothy to Charlestown, South Carolina to succeed the deceased Thomas Whitmarsh in publishing the South-Carolina Gazette, with a six-year publishing agreement whereby Franklin furnished the press and other equipment, paid one-third of the expenses, and was to receive a third of the profits from the enterprise. The South-Carolina Gazette resumed weekly publication under Timothy’s name on February 2, 1734.

Lewis became the official colonial printer and his family were members of St. Philip’s Church Lewis became a founder and officer of the South Carolina Society, a social and charitable organization made up of Huguenots. Lewis organized a subscription postal system originating at his printing office and by 1736 he obtained land grants totaling six hundred acres and a town lot in Charleston.

Lewis died during the Christmas season of 1738 with a year remained on his contract with Franklin. The contract provided for Timothy’s son, Peter, to carry on the business until the contract expired. Due to Peter’s youth, Lewis’s wife, Elizabeth Timothy, assumed control of the printing operation and published the next weekly issue of the South-Carolina Gazette. The publisher, however, was listed as Peter Timothy.

In the first issue of the Gazette, Elizabeth Timothy informed readers that it was customary in a printer’s family in the colonies and in Europe for wife and sons to help with the printing operation. So it isn’t surprising that Elizabeth was able to continue the work of her husband, with the help of her son Peter, then only 13 years old. Elizabeth wrote:

“Whereas the late Printer of this Gazette hath been deprived of his life, by an unhappy accident, I shall take this Opportunity of informing the Publick that I shall continue the said Paper as usual; and hope, by the Alliance of my friends, to make it as entertaining and correct as may be reasonably expected.”

Elizabeth Timothy, as Official Printer for the Province, printed acts and other proceedings for the Assembly. In addition to the Gazette, she printed books, pamphlets, tracts, and other publications. Although the colophon “Peter Timothy” appeared after each, there was no doubt who made most of the decisions in the operation of the business.

Years later, in his autobiography, Franklin described Lewis Timothy as “a man of learning, and honest but ignorant in matters of account; and tho’ he sometimes made me remittances, I could get no account from him, nor any satisfactory state of our partnership while he lived.” On the other hand, he had only praise for Elizabeth Timothy. Franklin wrote she “operated the Printing House with Regularity and Exactitude …and manag’d the Business with suck Success that she not only brought up reputably a Family of children, but at the Expiration of her Term was able to purchase of me the Printing House and establish her Son in it!”

When Peter Timothy turned 21 in 1746, he assumed operation of the Gazette. Prior to taking over the publishing, he married Ann Donavan and their union produced twelve children. His mother opened a book and stationery store next door to the printing office on King Street. She died on April 2, 1757, and was buried at St. Philip’s. Elizabeth Timothy is now recognized as America’s first female newspaper editor and publisher and one of the world’s first female journalists. She was inducted into the South Carolina Press Association Hall of Fame in 1973. A plaque recognizing her unique role in South Carolina business and journalism occupies a spot “on the bay near Vendue Range,” where she last served as publisher of the South-Carolina Gazette. She was inducted into the South Carolina Business Hall of Fame in 2000. She was also featured in my book CHARLESTON FIRSTS.

Her son, Peter, became one of the most widely known Southern journalists of the 18th century. He became postmaster general for Charleston in 1756, and during the Stamp Act Crisis he became deputy postmaster of the southern colonies. Under his guidance, the South-Carolina Gazette became increasingly partisan in the colonial crisis, criticizing Governor James Glen, and supporting the Wilkes Fund. He passionately condemned the Boston Massacre.

He carried on the publication of the Gazette continuously as publisher or proprietor until February 1780, citing his closure due to lack of material due to the British blockade of Charlestown. On the second of August 1776, Timothy began printing the Declaration in the form of broadsides, which would be hung in public places, such as churches, in order to distribute the bold establishment of a new country, separate from Great Britain. It is unknown if Timothy printed several copies which were then destroyed or if he only printed one, as the copy in the Gilder Lehrman Collection is the only known existing copy printed by Timothy. It is also the only surviving copy of the Declaration that was printed south of Philadelphia.

Timothy’s printing of the Declaration had repercussions. In 1780, after the fall of Charlestown to the British, he was arrested for treason by the British and was one of twenty-eight Carolina patriots sent to a prisoner-of-war ship and ultimately, exiled in prison in St. Augustine, Florida.

In 1782, rather than return to Charlestown, Peter Timothy decided to explore the possibility of settling in Antigua. However, during the voyage, his ship sank in a gale off the Delaware capes, and everyone on board drowned.

Peter’s wife, Ann Donavan Timothy, returned to Charlestown and resumed publication of her husband’s newspaper on July 16, 1783, on Broad Street. Nine years later, she was succeeded as publisher by Benjamin Franklin Timothy, her son and Elizabeth Timothy’s grandson.

Thus we have two women in Colonial America, who took over their husband’s career as publisher/editor of the most important publication in the South during that time.