1781 – Births

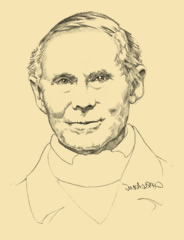

During a 50+ year career as an architect and engineer, Robert Mills left his legacy across the United States.

Robert Mills was born in Charlestown on August 12, 1781, during the British occupation of the city. His father was a tailor, respectable and successful but solidly middle class. Mills is often erroneously referred to as America’s first native-born architect, but Charles Bullfinch of Boston, has a clearer claim to that honor.

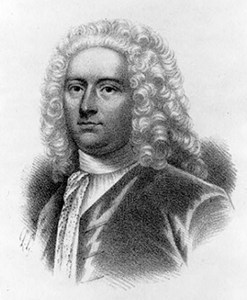

When Robert Mills was ten years old, President George Washington visited Charleston for seven days. While in the city Washington inspected the almost completed Charleston County Courthouse and was impressed by its young Irish architect, James Hoban of Philadelphia.

During his time in Charleston (1787-1792) Hoban conducted an “evening school, for the instruction of young men in Architecture.” It is often speculated that Mills attended these classes, but there is no documentation of that fact. If not, then due to the quality of his earliest drawings (1802), certainly Mills would have attended similar classes offered to young men in Charleston. Newspapers at the time advertised that M. Depresseville:

Continues to keep his Drawing School, in different Part of Landscapes, with Pencil or Washed, teaches Architecture, and to draw with method; also the necessary acknowledgements for the Plans.

Another advertisement claimed that Thomas Walker, a stone cutter and mason from Edinburgh:

opened an evening school for teaching the rules of Architecture from seven to nine in the evening (four nights a week)

In 1800, at age nineteen, Mills moved to Washington, D.C. and was hired by James Hoban. The Irish architect who had so impressed George Washington in Charleston, had won the design competition of the President’s Palace – the White House. In December 1800 Mills was “pursuing studies in the office of the architect of the President’s House.”

Under Hoban, who was also at the same time supervising the construction of the Capital, Mills served as an apprentice or assistant and spent most of his time drawing and sketching wainscot, staircases and doorways, and learning the more rudimentary skills of construction – labor and material management. During the next two years Mills was exposed to more building and design than he could have in any place in America.

Mills also befriended Thomas Jefferson during this time and wrote that Jefferson “offered me the use of his library.” He also wanted drawings of his home, Monticello and he “engaged Mr. Mills to make out drawings of the general plan and elevation of the building.”

In 1802, Mills submitted designs for the proposed South Carolina College and won the $300 prize, even though none of his designs were ever used. He then spent eight years working for Benjamin Latrobe who had been appointed Surveyor of Public Buildings by President Thomas Jefferson.

Mills wrote that Latrobe was:

Engaged upon the Delaware and Chesapeake Canal and as an architect of the Capitol at Washington, at which time I entered his office as a student under the advice and recommendation of Mr. Jefferson, then President of the United States.

Latrobe later described Mills as possessing:

that valuable substitute for genius – laborious precision – in a very high degree, and is therefore very useful to me, though his professional education has been hitherfor much misdirected.

During this time Mills also submitted plans for two Charleston churches, an alteration of St. Michael’s (never implemented) and a design for the Congregational Church. Dr. David Ramsay presented the idea of a round church in 1803 saying his “wife suggested the idea and sketched a plan.” In February 1804 the church’s building committee thanked Mills:

for his ingenious and elegant drawings which had essentially assisted the Members and Supporters in forming a correct opinion of the form and plan of their proposed building.

Mills plans called for a rotunda eighty-eight feet in diameter and thirty-three feet high, covered by a hemispherical Delorme made of wood and sheathed in copper, capped by a large cupola. His design for the church was severely altered when the church was constructed in 1806, much to Mills’ displeasure

Ruins of the Circular Congregational Church, Charleston, circa 1880s. Photograph shows the damage from the 1861 fire that ravaged the city. Courtesy Library of Congress.

In 1819 South Carolina established an Internal Improvements Program for the creation of canals, roads and public buildings. With a budge of $1 million spread out over ten years it was the largest public works improvement project per capita of any state in America. Mills was hired as the Acting Commissioner for Public Buildings. His main task was to design (or redesign) courthouses and jails across the state. However, the state legislature had noted the need for fireproof buildings as repositories throughout the state and appropriated $50,000 for the design and construction.

On May 20, 1822, Charleston City Council voted to pay Mills $200 for a fireproof building on the square behind City Hall to be used for county records. Mills envisioned the building as part of a public square which embraced the park (later named Washington Park), City Hall, the County Courthouse and a proposed Federal courthouse.

In December 1823 Mills lost his post as Superintendent of Public Buildings but was appointed as one of four “Commissioners for completing Fire Proof Buildings.” He was also appointed Commissioner of Public Buildings for Charleston District, even though he was living in the state capital, Columbia.

Throughout 1825-26, under the supervision of contractor John Spindle, the construction of the Fireproof Building continued. All materials were non-flammable – granite, brownstone, flagstone, brick, metal and copper. On December 11, 1826, it was finished and “ready for occupancy.” Final cost of the project was $53,803.81.

In 1836, Robert Mills won a private design competition conducted by the Washington National Monument Committee for a permanent memorial to George Washington in the nation’s capital. His original design called for a 600-foot-tall square shaft rising from a Greco-Roman circular colonnade of thirty Doric columns, 45 feet high and 12 feet in diameter.

By the time the cornerstone was laid on July 4, 1848, the design of the monument had changed considerably to the more stream-lined, elegant structure that is one of the most famous landmarks in the United States.

Mills died on March 3, 1855 with more than 50 projects to his credit, which include more than thirty county courthouses and jail buildings in South Carolina. Some of Mills’ most important projects include:

1804

- Circular Congregational Church, Charleston, S.C.

1806

- South Carolina Penitentiary, Columbia, S.C.

1809

- Franklin Row, Philadelphia, Pa

- State House (Independence Hall) Wings, Philadelphia, Pa.

1812

- First Unitarian (Octagon) Church, Philadelphia, Pa

1813

- Washington Monument, Baltimore, Md.

1816

- Winchester Monument, Baltimore, Md.

- First Baptist Church, Baltimore, Md.

1817

- John’s Episcopal Church, Baltimore, Md.

1818

- First Baptist Church, Charleston S.C.

1821

- Colleton County Courthouse; Colleton County Jail, Walterboro, S.C.

- Columbia Canal, Columbia, S.C.

1822

- Charleston County Jail (addition), Charleston, S.C.

- County Records Office – Fireproof Building, Charleston, S.C.

- Powder Magazine Complex, Charleston, S.C.

- South Carolina Asylum, Columbia, S.C

1823

- Horry County Courthouse and Jail, Conway, S.C.

- Union County Courthouse, Union, S.C.

1824

- Peter’s Church, Columbia, S.C.

- Maxcy Monument, Columbia, S.C.

1825

- Atlas of the State of South Carolina

- Edgefield County Courthouse, Edgefield, S.C.

1826

- Elevated railroad, Washington, D.C. to New Orleans

- Newberry County Jail, Newberry, S.C.

1830

- U.S. Senate (renovation), Washington, D.C.

1831

- Marine Hospital, Charleston, S.C.

- Washington Canal, Washington, D.C.

1832

- Executive Offices and White House (water systems), Washington, D.C.

- House of Representatives (alterations), Washington, D.C.

1833

- Customs House, New London, Ct.

- Customs House, New Bedford, Ma.

1834

- U.S. Capital (water system), Washington, D.C.

1836

- U.S. Patent Office, Washington, D.C.

- South Caroliniana Library, Columbia, S.C.

- U.S. Treasury Building, Washington, D.C.

1839

- Library and Science Building, U.S. Military Academy, West Point, N.Y.

- U.S. Post Office, Washington, D.C.

1845

- Washington National Monument, Washington, D.C.

1847

- Smithsonian Institution (supervising architect), Washington, D.C.

1852

- University of Virginia Library (addition, renovation), Charlottesville, Va.

1863 – Civil War. H.L. Hunley Arrives

The Hunley submarine arrived in Charleston. James McClintock, one of the designers and builders of the Hunley was offered $100,000 ($1.6. million in current currency) to sink either the New Ironsides or the Wabash, two of the Federal ships in the blockade. With a crew of volunteers, the McClintock conducted a week of safe tests in the harbor between Ft. Johnson and Fort Moultrie, away from the eyes of the Federal blockade. Gen. Beauregard quickly became frustrated by McClintock’s caution. He asked that a Confederate Navy man sail on the submarine. When McClintock refused, Beauregard ordered the submarine seized by the Confederate Navy and a crew of volunteers take over its operation.

McClintock was so disgusted he left Charleston.