In Charleston, change is often a four letter word. More than any American city, Charleston guards its heritage with a passion. In 1861, South Carolina, led by Charleston men, attempted to start its own country in order to preserve its way of life. During the early part of the 20th century, while the rest of America was embracing the future, Charleston was focused on the past.

Rainbow Row, East Bay Street, Charleston, SC

In 1922 a petition was sent to Charleston City Council signed by thirty-seven white residents around Church Street and St. Michael’s Alley which called for the immediate evacuation of the all-black residents of Cabbage / “Catfish” Row. The petition detailed the unsavory behavior of the black residents that included prostitution of black women with white sailors, knife and gun fights, unsanitary conditions and “the most vile, filthy and offensive language.” The Powder Magazine (17 Magazine St) was preserved; Susan Pringle Frost began purchasing the slums along eastern Tradd Street for renovation, creating Rainbow Row; Congress authorized the transfer of the Old Exchange Building (122 East Bay St.) to the Daughters of the American Revolution; the Society for the Preservation of Old Dwellings was established; the Joseph Manigault House opened as the first house museum and the Heyward-Washington House was purchased by the Charleston Museum.

George Gershwin and Debose Heyward on Chalmers Street, Charleston, SC

For many white Charlestonians, the ubiquitous presence of Gullahs was as common as palmetto trees – visible on each street but rarely acknowledged, just part of the scenery. The city had spent 70 years after the War trying to preserve white Charleston heritage. But now, the Gullah heritage was what most Americans associated with the city. The dance called the “Charleston” became the symbol of the Roaring 20s and Heyward’s story of a doomed love affair between a black prostitute and beggar became a cultural event.

In the spring of 1924, Dubose Heyward, founder of the Poetry Society of South Carolina, began working on “a novel of contemporary Charleston.” Heyward had a reputation across America as a serious and talented poet and Charleston society was rightly proud of their native son. The perception was that his forthcoming novel of would be a drawing room drama, or a comedy of manners. It was going to be about them. Imagine their shock when the book, Porgy, was a lyrical folk novel about the Gullahs of Charleston and became very successful. And then it became the Gershwin “Negro folk opera,” Porgy and Bess.

The Chicago Tribune wrote:

In a world of change, Charleston changes less than anything …. Serene and aloof, and above all permanent, it remains a wistful reminder of a civilization that elsewhere has vanished from earth.

The success of Porgy and Bess instigated another Yankee invasion, and this time they brought cash. With the Depression gripping America, Charleston was grateful for any money it could earn. The mostly pre-Revolutionary residential area of Heyward’s former neighborhood – Church and Tradd Streets – became a haven for tourist shops, catering to the much-disdained, but much-needed Yankee trade. Ladies of “quality” from Charleston’s “first families,” ran coffee houses and tea shops and served as “lady guides” on walking tours down the cobblestone streets and brick alleys. Their version of Charleston was completely focused on the glory days of the past, discussing “servants” not slaves, architecture not secession. They were trying to preserve, or more realistically, resurrect, what Rhett Butler described in Gone With The Wind as “the calm dignity life can have when it’s lived by gentle folks, the genial grace of days that are gone.”

Led by two community boosting mayors, John P. Grace and Thomas Stoney, this refocusing of history has finally reached into the 21st century. The 1930s preservation and tourism campaign solidified Charleston’s image as “America’s Most Historic City” and now in the 21st century, it is the darling of the upscale international tourist trade.

Kendra Hamilton wrote:

The ironies of the situation are compelling. Charleston becomes daily more segregated, the chasm between rich and poor ever deeper and wider, as in the salad days before the war. The tourist-minded city fathers become daily more ingenious at smoothing down the ugly truths of the city’s history so as to increase its appeal to people whose impressions of the South owe more to Scarlett O’Hara than Shelby Foote. And yet, the city’s most readily identifiable cultural emblems – from Porgy to “the Charleston” – have African-American roots.

Porgy House. Dubose Heyward’s home on Church Street where he wrote the novel, “Porgy.”

Charleston learned it was easier to protect its buildings than its social and cultural heritage. An ordinance may preserve a historic house, but it cannot alleviate the historic truth. During the 21st century Charleston finally fully embraced its rich cultural African heritage, mainly due to the explosion of the national popularity of southern food and “low country cuisine.” Southern food is, without a doubt, African food.

During the 1930s and 40s DuBose Heyward’s former home at 76 Church Street became the Porgy Shop, which sold antiques, china curios and other fine furnishings that had nothing to do with the opera, the play, or the novel. It certainly had nothing in common with its namesake, a poor, violent black beggar turned into a folk hero. In another ironic twist, the “first families” of Charleston who made money from this skewed, picturesque version of history, did not even allow a version of their most famous commodity to be performed in its home setting until 1970, thirty-four years after its debut.

However, there is also the gradual deterioration of another one of Charleston’s longest traditions – merriment! In 1989, Hurricane Hugo blew out the Spanish moss and blew in the insurance money (and upscale tourists.) From that moment Charleston began its march toward becoming a tourism-centric culture with a heavy concentration on luring the sophisticated traveler. The less gentile aspects of the city have been incrementally discarded, and the city enforces their “merriment” rules with some inconsistency.

- No more street parties on St. Patrick’s Day. The only approved street “parties” these days are politically correct cultural events like the Art Walk (even then you can’t carry your topless plastic cup from site-to-site,) the MOJO Arts Fesitval and various SPOLETO and Piccolo Spoleto happenings.

- No smoking in ANY building in Charleston. For a city with world class restaurants and bars, the non-smoking ordinance is not only heavy-handed, it is elitist.. After the passing of the non-smoking ordinance Club Habana (the city’s ONLY smoking club) was allowed to operate under a grandfathered-in clause, but the club lost its lease and was squeezed out of the ever-more bland and gentrified City Market.

- Tailgating at Citadel football games is allowed 2 hours before and 2 hours after the game. However, fireworks at 11 pm after a baseball game in a park named after the current mayor(and close to the football stadium and a residential neighborhood) is allowed.

- Open-container laws are strictly enforced in Charleston’s historic district and in the Market. However, during the internationally promoted Food & Wine Festival, patrons are allowed to walk about Marion Square with open cups of wine.

By the 1980s all of the “adult clubs,” “massage parlors” and by-the-hour hotels that used to be located around the Market area were pushed to the extreme northern end of the city and replaced by more and more restaurants with similar menus and upscale shops selling merchandise more New York than southern.

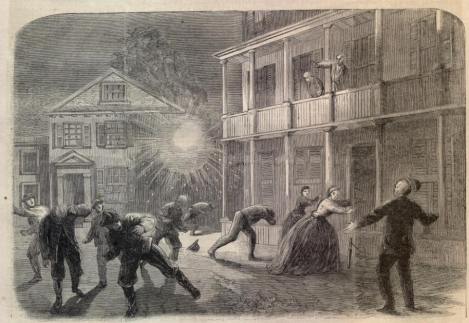

The Tavern, 120 East Bay Street.

During the 1990s, as the price of real estate began to rise in the downtown area, a new crop of self-important persnickety puritans arrived and have slowly strangled the real social character of Charleston, with the support of the city officials. After all, we can’t allow blue collar drunks on the streets of the Holy City having fun, can we?

Well, yes we can, and we always have. Charleston is called the Holy City due to its number of churches, not due to the behavior of the locals. Maybe if these persnickety puritans had taken the time to learn the “real” heritage of their new city BEFORE they decided to purchase that million dollar home, things might be different.