1768

Colonial Lake, a Charleston landmark established by the Commons House of Assembly, encompasses a city block in the midst of two neighborhoods. It was one of several public works projects initiated under Gov. Charles Greville Montagu. The original commissioners are names that still well-known in Charleston today: Henry Middleton, Isaac Mazyck, Rawlins Lowndes, Edward Fenwick, William Henry Drayton, Arthur Middleton and William Savage.

Colonial Lake, a Charleston landmark established by the Commons House of Assembly, encompasses a city block in the midst of two neighborhoods. It was one of several public works projects initiated under Gov. Charles Greville Montagu. The original commissioners are names that still well-known in Charleston today: Henry Middleton, Isaac Mazyck, Rawlins Lowndes, Edward Fenwick, William Henry Drayton, Arthur Middleton and William Savage.

The Colonial Commons Commission was established to oversee the lake area, specifically to:

authorize Commissioners to cut a canal from the upper end of Broad Street into Ashley River; and to reserve the vacant marsh on each side of the said canal, for the use of a common for Charlestown.

1770: American Revolution – Foundations

The Townsend Acts were repealed by Parliament. However, in an effort to avoid the appearance of weakness in the face of intense colonial protest, the tea tax was left in place.

1861 – Civil War – Firing on Fort Sumter – Charleston First

After contacting his superiors in Montgomery, Beauregard wrote another dispatch and about midnight, his aides rowed out to Fort Sumter again flying a white flag. His response to Anderson was:

MAJOR: In consequence of the verbal observation made by you to my aides, Messrs. Chesnut and Lee, in relation to the condition of your supplies, and that you would in a few days be starved out if our guns did not batter you to pieces, or words to that effect, and desiring no useless effusion of blood, I communicated both the verbal observations and your written answer to my communications to my Government.

If you will state the time at which you will evacuate Fort Sumter, and agree that in the mean time you will not use your guns against us unless ours shall be employed against Fort Sumter, we will abstain from opening fire upon you. Colonel Chesnut and Captain Lee are authorized by me to enter into such an agreement with you. You are, therefore, requested to communicate to them an open answer.

I remain, major, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

G. T. BEAUREGARD, Brigadier-General, Commanding.

About 1:30 a.m. Anderson assembled his officers and read the Confederacy’s latest offer. For the next ninety minutes they discussed their response. They all considered the condition that they would not fire unless Sumter was shot at to be unacceptable. If the Federal supply ship arrived no doubt Confederate batteries would open fire upon it. The Federal officers were determined not repeat their lack of response during the Star of the West episode. But they were unsure of when (or even if) the supply ship would arrive. The officers agreed they could hold out four more days. Anderson composed his next reply to Beauregard:

GENERAL: I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt by Colonel Chesnut of your second communication of the 11th instant, and to state in reply that, cordially uniting with you in the desire to avoid the useless effusion of blood, I will, if provided with the proper and necessary means of transportation, evacuate Fort Sumter by noon on the 15th instant, and that I will not in the mean time open my fires upon your forces unless compelled to do so by some hostile act against this fort or the flag of my Government by the forces under your command, or by some portion of them, or by the perpetration of some act showing a hostile intention on your part against this fort or the flag it bears, should I not receive prior to that time controlling instructions from my Government or additional supplies.

I am, general, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

ROBERT ANDERSON, Major, First Artillery, Commanding.

The Confederate aides, Chesnut, Chisholm and Lee, read the reply immediately. Chesnut, following Beauregard’s orders, composed the following note:

SIR: By authority of Brigadier-General Beauregard, commanding the Provisional Forces of the Confederate States, we have the honor to notify you that he will open the fire of his batteries on Fort Sumter in one hour from this time.

We have the honor to be, very respectfully, your obedient servants.

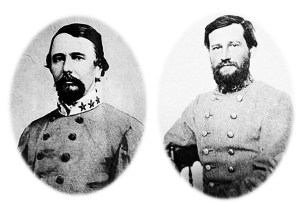

JAMES CHESNUT, JR., Aide-de-Camp.

STEPHEN D. LEE, Captain, C. S. Army, Aide-de-Camp.

Chesnut delivered the message to Anderson. After reading it, Anderson pulled out his pocket watch and checked the time – it was 3:20 a.m. He asked Chesnut, “I understand you, sir, then, that your batteries will open in an hour from this time?”

Chesnut replied, “Yes, sir. In one hour.”

Anderson walked the Confederate officers to their boat. It was beginning to rain. He shook hands with each of them. “Gentlemen, if we do not meet again in this world, I hope we may meet in a better one,” he told them.

Inside Fort Sumter Anderson ordered his men to prepare to receive an attack within the hour. He urged them to sleep if possible, that they would be returning fire at dawn.

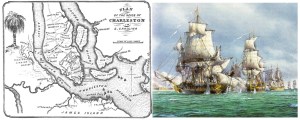

The Confederate officers made the one-mile journey from Fort Sumter to Fort Johnson within half an hour. Col. Chesnut told Captain George James, battery commander at Johnson, they had given Anderson a deadline, and it was to be met. He ordered a signal shot at 4:30 a.m.

Chestnut, James and Chisholm, anxious to return to Beauregard as soon as possible, then got back in their boat and began to row across the harbor to Charleston. Out in the middle of the water, in the drizzling rain, not a single star was visible against the dark forbidding sky. At exactly 4:30, Lt. Henry S. Farley pulled a lanyard on one of the cannons at the beach battery on James Island. A mortal shell arced high across the water, heading for Ft. Sumter, its glowing fuse leaving a glowing contrail, illuminating the sky. It exploded just above the fort like Fourth of July fireworks, spreading an orange-red glow across the horizon.

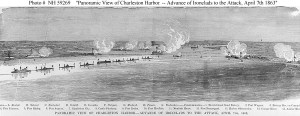

Confederate batteries at Fort Johnson fire on Fort Sumter, April 12, 1861. Courtesy Library of Congress

Within a minute of the signal shot, another shell screamed across the harbor and exploded within Fort Sumter. Beauregard had given precise orders on the firing rhythm. The forty-three guns that faced Sumter were each to fire in turn, in a counterclockwise circle, with two minutes between each shot, in order to save shot and powder.

In Charleston, Chesnut’s wife, Mary, was having a restless night. As she wrote in her diary:

I do not pretend to sleep. How can I? If Anderson does not accept terms at four, the orders are he shall be fired upon. I count four, St. Michael’s bells chime out and I begin to hope. At half-past four the heavy booming of a cannon. I sprang out of bed, and on my knees prostrate prayed as I have never prayed before … I knew my husband was rowing about in a boat somewhere in that dark bay, and that the shells were roofing it over, bursting toward the fort. The women were wild out there on the housetop.

In Charleston, the bombardment was a spectacle. As dawn broke, the streets were filled with people rushing in the rain to find a vantage point to watch the battle. The sea wall along the Battery was quickly crammed with ladies and gentlemen in their finest clothes. Boys scampered around, climbing on anything in an attempt to have a better view of the harbor.

There was not a single person who believed the Yankees would win.

Anna Brackett, a school teacher, described the scene in Charleston:

Women of all ages and ranks of life look eagerly out with spyglasses and opera glasses. Children talk and laugh and walk back and forth in the small moving place as if they were at a public show.

As dawn broke just after six, the Federal garrison at Sumter mustered for roll call and breakfast, which consisted mainly of salt pork. Private Joe Thompson wrote, “Our supply of foodstuffs are fast giving out. Yesterday our allowance was one biscuit.”

At 6:30 Capt. Doubleday ordered the first Federal shot in reply aimed at the Iron Battery at Cummings Point. It landed beyond the battery and into the marsh.

James Petigru, while sitting in his office at 8 St. Michael’s Alley wrote:

All the world is gone to witness the bombardment of Fort Sumter by the collective forces of South Carolina. Our politicians have succeeded in evoking the spirit of hostility on both sides.

By full light the rain had stopped and for the next two days, Fort Sumter was hammered from three sides by Confederate batteries, with more than 2,500 shots fired the first day. Overnight the bombardment slackened but resumed in full force the next morning.

Charleston (and America) would never be the same again.

1962

One hundred and one years after the first shot of the Civil War, Martin Luther King spoke at Mother Emanuel AMC Church, after several other local churches refused to allow him to speak there, fearing retribution.