1774

During the elections Francis Salvador was elected to the First Provincial Congress from the Ninety-six district – the first Jew elected to office in the American colonies.

1801

The legislature chartered South Carolina College, now the University of South Carolina.

1827

The Charleston & Hamburg Rail Road was chartered by Alexander Black and William Aiken. Black proposed to build and operate a railed road from Charleston to Hamburg Columbia and Camden.

Charleston’s economy heavily depending on the shipping of three staples: cotton to England, rice to southern Europe and lumber to the West Indies. The development of steamers that sailed the Savannah River that brought Georgia and South Carolina crops and goods from August to the port of Savannah, severely cutting into Charleston’s trade.

The proposed railed road from Hamburg (on the Savannah River across from Augusta) was considered the best solution – goods could be transported by rail 136 miles to Charleston.

1828 – Nullification Crisis. State’s Rights.

The South Carolina legislature adopted the Exposition and Protest (secretly written by Vice-President John C. Calhoun) which argued about the unconstitutionality of the Tariff of Abominations because it favored manufacturing over commerce and agriculture. Calhoun believed the tariff power could only be used to generate revenue, not to provide protection from foreign competition for American industries. He believed that the people of a state or acting in a democratically elected convention, had the retained power to veto any act of the federal government which violated the Constitution.

1860 – Second Day of Secession Convention

The Mercury’s front page exclaimed:

The excitement here is a deep, calm feeling … [the city] may be said to swarm with armed men [but] we are not a mobocracy here, and believe in law, order, and obedience to authority, civil and military.

Issac W. Hayne, the state’s attorney general, called for secession commissioners to be sent to other states, to urge them to join South Carolina. He called for each commissioner to carry a copy of South Carolina’s Ordinance of Secession, before it was even approved.

While the whites were celebrating, among the free blacks in Charleston, the exodus, which had started in September, continued. James D. Johnson, on Coming Street, was preparing his two houses for sale. He wrote, “I only want to beautify the exterior so as to attract Capitalists.” His son wrote, “It is now a fixed fact that we must go.”

At 11:00 a.m. the delegates met at St Andrew’s Hall. A delegate proposed that should “sit with closed doors,” and James Chesnut protested. He claimed that “a popular body should sit with the eyes of the people upon them.” He then suggested they move back to Institute Hall. John Richardson argued to Chesnut: “I protest. If there is one sentiment predominant over all others, and truly the mind of the people of Charleston, it is that this Convention should proceed!”

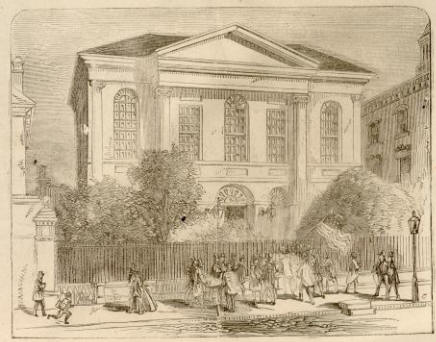

St. Andrews Hall, 118 Broad Street. Courtesy of Library of Congress

The doors were shut, locked and guarded by Charleston police. All the citizens could do was wait with the patience of a child on Christmas eve. An afternoon parade by the Vigilant Rifles and the Washington Light Infantry occupied some of the afternoon. They stopped in front of South Carolina Society Hall on Meeting Street, where Mayor Charles Macbeth presented a flag to Captain S. Y. Tipper “sewn by a number of the fair daughters of Carolina.” Capt. Tipper toasted Fort Moultrie:

It is ours by inheritance. It stands upon the sacred soil of Carolina, and the spirit of our patriotic fathers hover about it. Infamy to the mercenaries [Federal troops] that fire the first gun against the children of its revolutionary defenders.

The day ended, and no news from the convention. No ordinance yet.